STRATEGIC ASSESSMENT. At least 15 police officers and five civilians including a priest have been killed in coordinated attacks on two Orthodox churches and two synagogues in Russia’s North Caucasus republic of Dagestan on Sunday evening.

Russian law enforcement has deemed the attacks, which saw both police and National Guard officers deployed, as “acts of terror.”

The attacks are the latest incident involving the majority Muslim republic following an anti-Israeli mob at the republic’s main airport in October 2023 and the Moscow concert hall massacre of March 2024, which was partly carried out by Dagestani nationals and claimed by the Islamic State group. Gunmen launched the attacks almost simultaneously in Derbent, a city on the Caspian Sea coast, as well as in Dagestan’s capital Makhachkala.

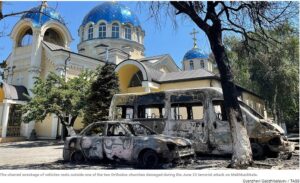

The attack took place on Pentecost Sunday, a holiday in the Russian Orthodox Church. In Derbent, unknown individuals got out of a white Volkswagen car and set fire to an Orthodox church and a synagogue located a few blocks apart. A police officer who attempted to stop the attackers was killed.

The Russian Jewish Congress said gunmen fired at police and security guards and threw in Molotov cocktails 40 minutes before evening prayers. It said that the brunt of the attack was suffered by local police and security guards who were stationed there following last year’s storming of Makhachkala airport.

At Derbent’s Orthodox church, attackers killed Father Nikolai Kotelnikov, a 66-year-old priest, and the church’s security guard.

The Govorit NeMoskva news outlet spoke with a local who described the priest as a beloved figure in the community.

“He was always ready to accept and listen, day and night. … This city did not lose a priest. The city lost its Father and became orphaned,” the local said.

In Makhachkala, attackers set the local synagogue on fire, the Russian Jewish Congress said.

Law enforcement was engaged in gunfights with the attackers for hours, with gunfire heard on the streets of both Derbent and Makhachkala.

Officials said police had killed four gunmen in Makhachkala and two in Derbent.

While the attackers’ identities have not yet been officially confirmed, they reportedly include two sons of the head of Dagestan’s Sergokalinsky district Magomed Omarov.

After his sons were killed during the anti-terrorist operation, Omarov was detained for further questioning, while law enforcement searched his home.

Omarov also casked to resign, but was swiftly dismissed by the ruling United Russia party and his records were promptly removed from the party’s website.

Another attacker was reportedly Gadzhimurad Kagirov, a freestyle wrestler who previously represented the Eagles MMA club, co-founded by former UFC Lightweight Champion and Makhachkala native Khabib Nurmagomedov.

“I think the biggest takeaway from the profiles of the shooters is that the radicalization pool just grew so much larger, and the Russian authorities are in a lot of trouble,” Harold Chambers, an analyst focusing on nationalism, conflict and security in the North Caucasus, told The Moscow Times.

“I am certain that Magomed Omarov has, by now, been repeatedly asked: ‘Your relatives were radicalizing, how could you have missed that?’ And that’s the thing, we have zero idea what is going on, and how big this thing is going to get,” he said.

An anonymous source told the Kremlin-backed RT network that Omarov was aware that his sons were sympathizers of Al-Qaeda, a banned terrorist organization, but that he did not disclose this information to either federal or Dagestani authorities.

The source added that the mosque frequented by the shooters and its imam are currently under investigation to find out if the mosque was a base of a Wahhabi cell.

More than 12 hours after the attacks began, Kremlin said that President Vladimir Putin does not plan to make a special address in response.

Asked whether Moscow feared a possible return to insurgent and terror attacks that marred the region in the early 2000s, Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov said: “No. Now there is a different Russia. Society is consolidated and such terrorist manifestations are not supported by society in Russia or in Dagestan.”

Dagestan’s leader Sergei Melikov wrote on Telegram that “we know who is behind these terrorist attacks and what objective they are pursuing,” without elaborating further.

“We must understand that war comes to our homes too. We felt it, but today we face it,” he said.

The authorities will try to find “all the members of these sleeper cells who prepared [the attacks] and who were prepared, including abroad,” he added.

Dagestan-born State Duma deputy Abdulhakim Gadzhiev, a member of the Security and Anti-Corruption Commissions, said without evidence that he had “no doubt” that the attacks were connected with the special services of Ukraine and NATO countries.

He was quickly criticized by Dmitry Rogozin, the ex-head of Roscosmos and current senator of Ukraine’s Russian-occupied Zaporizhzhia region, who wrote that the unfounded shifting of blame will “lead us to big problems.”

The state-run TASS agency cited sources as saying that the attackers in Makhachkala and Derbent were affiliated with an international terrorist organization.

The RBC newspaper corroborated this information with its sources in Dagestani security agencies and added that “several of the attackers were listed in the Interior Ministry databases as having connections in Wahhabi circles.”

Meanwhile, the Russian Union of Travel Industry recommended that tourists refrain from traveling to Dagestan until further notice.

Concerns over Islamist extremism were once thought to be a thing of the 1990s and early 2000s, and its defeat was touted as one of the proudest achievements of Putin’s presidency. However, following the Crocus City Hall massacre in Moscow in March, it has again become a pressing issue.

“This is absolutely part of a larger trend that’s been pretty obvious for several years now,” said Chambers. “While there’s been little data sociologically on support for extremist groups, Chechen political scientist and historian Mairbek Vatchagaev did do some sociological research on it, showing that there was actually increasing support for ISIS among Chechen youth.

“There is a generational turnover among the militants. Beyond that, especially over the past few years, the very obvious trend among popular North Caucasus resistance channels on Telegram is the embrace of more fundamentalist strains of Islam beyond traditional Sufism, going as far as to embrace Salafism or even Wahhabism,” he said.

Makhachkala hosted an anti-terrorist meeting between federal security officials and Dagestan leader Sergei Melikov. Meanwhile, Magomed Omarov himself hosted an anti-terrorist meeting in his municipality on April 25, which was attended by Dagestani security officials.

But Chambers said that the latest attacks underscore how authorities nonetheless failed to learn from the Crocus City Hall attack.

“The authorities still chased Ukraine’s specter rather than Islamic State and failed to curb the arms trafficking which is rampant in the nearby Krasnodar and Rostov regions, which was most likely the origin of the shooters’ weapons,” he said.

“Even more difficult is that unlike in Crocus, this attack presented different challenges, because it was carried out by a very tight-knit, local group,” Chambers said. “There were no longer any preemptive warnings from foreign intelligence groups that could assist in this situation, and neither was there the inclination on behalf of the Russian authorities to take the time to investigate potential terrorist cells within Russia.”

Dagestan is a majority Muslim republic in Russia’s North Caucasus region that is home to over 30 ethnic groups and 81 nationalities with 14 official languages.

It is one of the regions hardest hit by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and its mobilization for the war.

“The locals clearly understood that the mobilization would put their lives at risk, because they would be placed in positions on the frontline where they would be annihilated, and would receive no protections unlike the Kadyrovites,” Chambers said.

“This forced Melikov to double down and forbid public gatherings in all capacities, and further isolated Dagestanis to seek alternative information in digital spaces, where they were more likely to be exposed to radicalizing content,” he said.

Russia’s FSB security service in April said it had arrested four people in Dagestan on suspicion of plotting the deadly attack on Moscow’s Crocus City Hall concert venue in March, which was claimed by the Islamic State group.

Militants from Dagestan are known to have traveled to join IS in Syria, and in 2015, the group declared it had established a “franchise” in the North Caucasus.

Dagestan lies east of Chechnya, where Russian authorities battled separatists in two brutal wars, first in 1994-1996 and then in 1999-2000.

Since the defeat of Chechen insurgents, Russian authorities have been locked in a simmering conflict with Islamist militants from across the North Caucasus that has killed scores of civilians and police.