The foto has taken from IIke News Agency

A key point of debate about the invasion remains the premise of the attack – that Saddam Hussein’s regime, in contravention of UN Security Council resolutions enacted after his invasion of Kuwait in 1990, retained vast stockpiles of chemical and biological weapons, long-range ballistic missiles, and a nuclear weapons program. The invasion was a clear example of “preventive war” – military action taken to prevent a rival from gaining a capability that would grant them the upper hand. Coming 18 months after the catastrophic September 11, 2001, attacks on the United States by al-Qaeda, U.S. officials explained the Iraq intervention as a measure to ensure Saddam Hussein’s regime could never use WMD against the United States or transfer WMD to al-Qaeda or other terrorist groups. Yet, the Iraq Survey Group (ISG), a fact-finding mission established by coalition forces, found no significant WMD stockpiles in Iraq. In January 2004, the initial head of the ISG, David Kay, opened his testimony before the Senate Armed Services Committee with the statement: “Let me begin by saying, we were almost all wrong [about active WMD programs and stockpiles in Iraq], and I certainly include myself here.” The flawed justification for the invasion remains a source of widespread criticism and has been invoked to undermine U.S. criticisms of Russia’s war in Ukraine.

Even though the military intervention quickly ousted Saddam Hussein and his Ba’ath Party from power, the initial success was quickly undermined. As most experts predicted, the post-invasion U.S.-led de-Ba’athification policy, which expelled technocrats from government ministries and disbanded the military, collapsed the Iraqi government and fueled the nascent Sunni insurgency. Against this chaotic backdrop, a government dominated by Shia Arabs with long and extensive links to Iran and its Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) came to power. The groups that took prominence in successive Iraqi regimes included the Islamic Supreme Council of Iraq and the Da’wa Party – anti-Saddam Shia insurgent factions that received armed support from the IRGC during and after the 1980-88 Iran-Iraq War. The mainstreaming of these factions gave Tehran significant leverage inside Iraq following the U.S. invasion.

By 2006, at the height of the Sunni Arab insurgency and ethno-sectarian violence, Shia Arab politicians had amassed sufficient support to elect the leader of a Da’wa Party faction, Nuri al-Maliki as prime minister. Despite forming a moderate-sounding “State of Law” coalition, Maliki defied expectations of the U.S. officials still largely running Iraq’s government and security forces that he would bridge the Shia-Sunni Arab divide. This divide was further complicated by consistent tensions between the central government in Baghdad and the constitutionally autonomous government of Kurdish northern Iraq in Erbil. Maliki, partly at the behest of Tehran, pursued a mostly sectarian agenda reigniting a Sunni Islamist insurgency that had lost some of its momentum following the 2011 U.S. withdrawal. By 2014, the Sunni insurgency had rallied under the banner of Islamic State (ISIS) to seize major swaths of territory in northern and western Iraq. The insurgency quickly overwhelmed Iraqi security forces. A return of U.S military personnel and intensive rebuilding and retraining of Iraqi forces eventually regained the upper hand and defeated the ISIS challenge by 2018. Still, ISIS remains a potent force across the border in Syria and looks to take advantage of continuing resentment among Iraq’s Sunni Arab community.

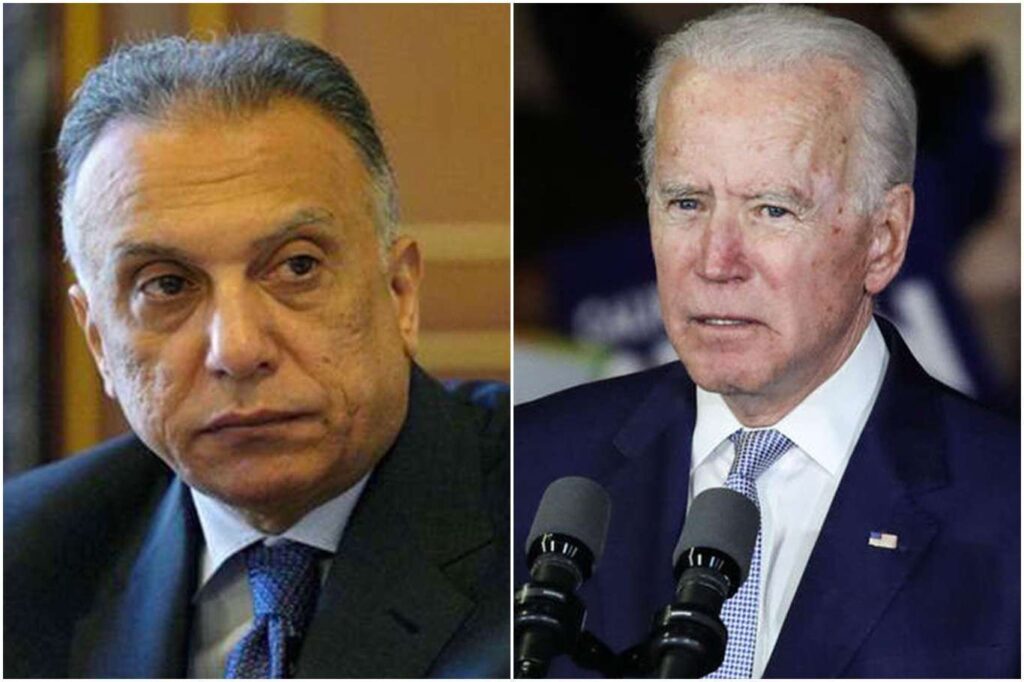

At the twentieth anniversary of the invasion, cautious optimism is emerging for Iraqi stability, regional integration, and government accountability. The national government has also identified addressing climate change as a growing priority. Although episodes of popular protests, punctuated by violent crackdowns, have seized Iraq in recent years, the political standoff between Moqtada al-Sadr and the larger Shia political community has been temporarily resolved. After a year of tense political maneuvering and brinksmanship, Prime Minister Mohammad Shiaa al-Sudani succeeded in forming a government this past fall. After more than 100 days in office he appears to be prioritizing stability over radical reform, pursuing populist policies, while appeasing elites, and maintaining a balanced foreign policy. Although his response to the astonishing theft of $2.5 billion from Iraq’s General Tax Commission has been lackluster, Sudani has taken tentative steps towards reducing endemic government corruption. Braving harsh criticism from his pro-Iranian collation members, al-Sudani has publicly committed to continuing Iraq’s security partnership with the U.S. He has also traveled to Tehran and met with the IRGC’s Quds force commander. Unless Iran-backed militia groups act as spoilers, Sudani may be able to maintain constructive relationships with the United States and Iran.

Sudani is also pushing to enact a long-stalled hydrocarbon law that would pave the way for new foreign investment in Iraq’s energy sector and hopefully resolve seemingly intractable disputes between Baghdad and Erbil. Even without the new law, the oil sector has been attracting U.S. and other outside investment and is powering economic growth. With oil prices soaring, the government took in approximately $114 billion in oil revenues in 2022, a massive increase over its pandemic-low of $42 billion in 2020. These revenues have helped PM Sudani accommodate his rivals and allies. At the same time, however, there are legitimate concerns over the viability of Iraq’s public budget, 90 percent of which is funded by oil sales. Without concerted efforts to diversify Iraq’s economy, a price shock could extinguish the newfound stability, plunging Iraq’s government back into crisis mode.

Having brokered several rounds of talks between Saudi Arabia and Iran, Iraq is working to reintegrate itself into the Arab fold. High-ranking Iraqi officials now regularly attend multilateral meetings in Arab capitals, and Foreign Minister Fuad Hussein visited Washington for a week-long visit in February to map out U.S.-Iraq cooperation going forward. U.S. officials now say that Iraq is a strategic asset to the region, rather than the threat that the country posed under Saddam Hussein. Still, PM Sudani’s political alliance with ex-Prime Minister Maliki has prompted U.S. officials to watch for signs that his government might again try to marginalize the Sunni Arab community and provide fuel for an ISIS resurgence. Twenty years after the invasion, Iraq remains fragile, but its resilience and resistance to taking unquestioned directionfrom Tehran are exceeding expectations.