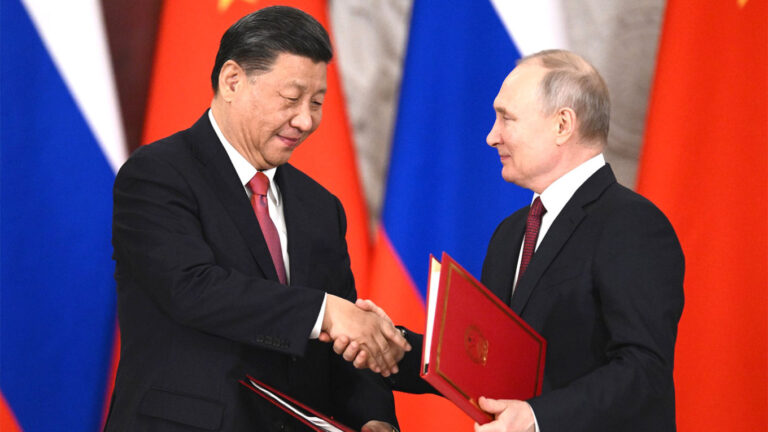

Thousnads of demonstrators gather at the Kasba in Tunis on Febuary 25, 2011. Tens of thousands of Tunisians rallied today to demand the resignation of Prime Minister Mohamed Ghannouchi's transitional government set up after last month's ouster of Zine el Abidine Ben Ali. AFP PHOTO / BORNI Hichem (Photo credit should read BORNI Hichem/AFP/Getty Images)

STRATEGIC ASSESSMENT. On 25 July, 2022, Tunisians approved a new constitution that solidified the rule of President Kais Saied and quelled hope for the preservation of multiparty democracy in the North African country. The new charter will further enshrine the one-man rule of President Saied, initially a technocrat who has now consolidated power over the past year. Since July 2021, he has fired the prime minister, dissolved Tunisia’s parliament, and suspended the 2014 constitution. The constitutional referendum, which weakens parliament and most checks on the president’s power, was marred by widespread boycotts. Moreover, with less than 30 percent of Tunisians turning out for the referendum, some have described the vote as farcical and illegitimate. The new constitution also provides Saied with the authority to appoint government ministers and judges without parliamentary approval. Saied summarily dismissed dozens of judges, some of whom have gone on hunger strike in protest and remain in dire condition. The mounting concerns about Tunisia’s lurch towards authoritarianism have now crystallized. Many of the key reforms made in the wake of the 2011 Jasmine Revolution and Arab Spring have been rolled back or eliminated entirely.

Tunisia was the only country to codify increased political freedoms and maintain a stable government following the Arab Spring revolutions. In other states where uprisings occurred—Bahrain, Egypt, Libya, Syria, and Yemen—new leaders reflexively employed autocratic tactics to lessen the ensuant chaos, with claims of countering terrorism. The birth pangs of Tunisia’s democratic transition in the wake of the Arab Spring meant struggles with job production, corruption issues, and other necessary reforms that were slow to materialize; already before the referendum there were clear indications of trouble. Arab Barometer surveys showed Tunisians shrinking confidence in democracy to deliver on the provision of basic goods and services. These same issues are still at the forefront of the political agenda for most Tunisians, who remain concerned about employment, food security, and the costs associated with rising inflation. As violence and terrorism continue to expand across the Sahel, there are also concerns about the regional impacts of increased instability in a key state seen as a potential model for achieving genuine political transformation without violent upheaval.

U.S. State Department spokesperson Ned Price observed Tunisia’s low voter turnout and suggested that civil society organizations within the country were worried about “the lack of an inclusive and transparent process and limited scope for genuine public debate during the drafting of the new constitution.” Some have accused Saied of fearmongering and attempting to scare moderate Tunisians by suggesting that Ennahda, the Islamist political party, would return to power if voters failed to support the new constitution, exploiting concerns about the influence of Islamists over social and political life in the country. Over the past year, Saied has displayed an authoritarian streak, jailing political opponents and restricting the independent media in an attempt to clamp down on dissent. For many Tunisians who support Saied’s power grab, economic stability is the overarching concern; rising food insecurity globally will likely keep these concerns at the forefront. To have any chance of remaining in power, Saied will have to focus on timely and tangible benefits.

The democratic backsliding of yet another post-Arab Spring state could dampen the prospects of future revolutions and democratic reform movements. Many throughout the Middle East and North Africa, especially younger generations, will likely see the power grab in Tunisia as a critical blow to the viability of pluralism and democracy in the region. The failed democratic transitions in Arab countries could very well strengthen the hand of violent non-state actors in the region, including jihadist groups linked to al-Qaeda or the Islamic State (ISIS), who have long argued that the only way to eliminate corruption and improve governance in the region is to subscribe to their views and foster violent change. Nearly 3,000 Tunisians left to fight with the Islamic State, although upwards of 27,000 had attempted to join, demonstrating just how much ISIS’ ideology resonated with Tunisians. Certain towns, including Ben Gardane along the Libyan border, were disproportionately overrepresented within groups like ISIS. Tunisia has also suffered at the hands of terrorists, with high-profile attacks at the Bardo National Museum in Tunis in March 2015 and at a beach resort at Port El Kantaoui, just north of the city of Sousse in June of that year. There have been other shootings and suicide attacks in the years since, which has had a negative impact on tourism in the country, another economic body blow. As conditions deteriorate, and citizens look to the success of other predatory governments, including some efforts to normalize the Assad regime despite the horrors of the Syrian civil war and the current political turbulence in Iraq the prospects for democratic change and the development of truly diverse and inclusive political process could be diminished for several decades.