Jangan Golput di Pemilu 2024

STRATEGIC ASSESSMENT. In a month’s time some 204m Indonesians can vote in a first round to choose their new president. Two of three presidential candidates are emblematic of reformasi—that is, the era of often impressive democratic development since the fall of Suharto, the long-ruling late dictator, in 1998. Ganjar Pranowo, who is 55, and Anies Baswedan, 54, have records as competent elected leaders, respectively as governor of Central Java and as governor of Jakarta, the capital.

Both are well educated. Their agendas, in a conservative majority-Muslim country, are broadly secular and liberal, and they stress the rule of law. Unlike other powerful politicians, neither is from a military-and-business dynasty.

Then there is Prabowo Subianto, the problematic favourite. He is polling at 43%, versus 25% for Mr Anies and 23% for Mr Ganjar. After President Joko Widodi, known as Jokowi, who is stepping down, the 72-year-old is the country’s most recognised politician.

A former general from a powerful family, he has long revelled in a strongman image—like Mussolini, he rarely appears happier than when astride a white charger. He is immensely rich, with fingers in many pies. He has contested three presidential elections but never been elected to public office. After Jokowi defeated him twice, the outgoing president made Mr Prabowo his defence minister in 2019.

Professor Vedi Hadiz, Director of the Asia Institute, University of Melbourne said Prabowo Subianto, the front-runner among the three men vying for the Indonesian presidency, has a major gripe. At the first presidential candidates’ debate, held in Jakarta in December, he complained that there was always someone who questioned his human rights record whenever he ran for office and was up in the polls. He had a point. But so do his detractors, though perhaps not the one they necessarily mean to raise.

Within the rather cloistered community of Indonesian politics-watchers, there has long been a debate about what to make of the changes since the fall of the authoritarian New Order in 1998 and the advent of democratisation. Lots of theories have been thrown around, from ‘democratic transitions’ and ‘consolidations’, all the way to ‘cartelisation’ and ‘oligarchy’. Today, whatever their theoretical standpoint, just about everybody agrees that Indonesia has taken many steps backwards in a democratisation process once greeted almost euphorically, although they may differ on how to explain it.

That Prabowo—son-in-law of Suharto, New Order-era general, and alleged perpetrator of human rights abuses from Papua to East Timor to Jakarta—is the current presidential front-runner does speak volumes. More so, because paving the way for him has been no less than President Joko Widodo (Jokowi), whose ascendancy to the presidency in 2014 had warmed the hearts of those who preferred to see ruptures as over-riding the continuities in Indonesian politics.

Leonard C. Sebastian, Senior Fellow and Coordinator of the Indonesia Programme at the Institute of Defence and Strategic Studies, S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, and Januar Aditya Pratama, Research Analyst with the Indonesia Programme at the Institute of Defence and Strategic Studies, S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, like the elections of 2014 and 2019, which saw the emergence of social media influencers and, to some extent, the so-called “buzzers”, the impact of social media on the 14 February presidential election will be evident; however, it will have its own merits and challenges.

While the threats of both disinformation and misinformation persist, there are novel dynamics shaping the 2024 presidential election in Indonesia, namely, the proliferation of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning, with its impact of producing more combustible dynamics on social media, and, unlike during previous elections, the presence of a more diverse electorate.

People of the Gen-Z generation alone comprise more than 23% of the electorate; combined with millennials, they constitute the majority of voters. Furthermore, these two generations dominate the internet and, by extension, social media.

Consequently, the candidates competing for the presidency this year have tailored their campaigns to fit the demands and needs of the youth, especially first-time voters. Such conditions, in turn, provide unique opportunities and challenges.

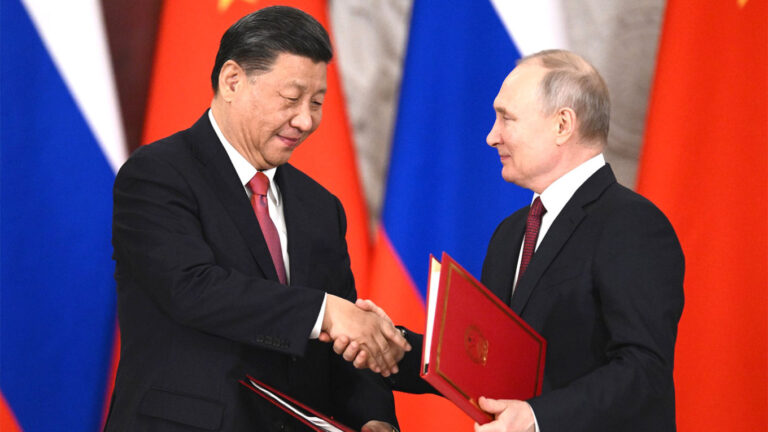

Moch Faisal Karim, The Jakarta Post, the recent presidential debate, centered around the Indonesia’s position in international affairs, may not have captivated the public, who often prioritize issues like the economy and corruption. However, the candidates’ views on foreign policy offer a profound insight into their broader vision for Indonesia’s role on the world stage.

Worldviews in international relations typically fall within two major spectra: Hobbesian and Grotian. The Hobbesian perspective, rooted in realism, perceives the state position at the global level through the lenses of military and economic might. It is a self-help system where states prioritize their own survival and interests, measuring their influence by material capabilities.

For middle powers, this translates into an influence shaped by military strength and economic resources in an environment rife with inevitable conflict. This also implies an influence directly proportional to their military prowess and economic clout.