STRATEGIC ASSESSMENT. As the war in Ukraine rages on, the United States and its allies are laser-focused on great power competition with near-peer states, especially China. In terms of policy bandwidth and resource allocation, counterterrorism has been relegated to a second-tier priority. This is true even as the global terrorist threat continues to evolve and assume new forms, and intersects closely with geopolitical dynamics in many contexts. There appears to be a growing sense of complacency in the West, with declining numbers of jihadist attacks and resulting casualties on Western soil. According to the recently released EUROPOL Terrorism Situation and Trend Report (TE-SAT) for 2022, “terrorism remains a significant threat to the internal security of the European Union,” but at the same time, in 2022, there were two jihadist terror attacks and just one far-right attack in Europe, resulting in four deaths. The majority of attacks were attributed to left-wing and anarchist terrorism, demonstrating the changing nature of terrorism in Europe. Still, the ongoing war in Ukraine, Taliban rule in Afghanistan, reports of ISIS remains regrouping in the Levant and numerous other factors and drivers will likely further impact the terror landscape in the West and more broadly going forward.

Another recently released report, this one by the United Nations ‘1267’ Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team, laid out a dire picture of the situation in Afghanistan. The relationship between the Taliban and al-Qaeda in Afghanistan remains “strong and symbiotic.” While al-Qaeda’s numbers are modest—believed to be an estimated 400 militants in the country—the threat is far from static. On the contrary, the UN report notes that under Taliban supervision, al-Qaeda is establishing new training camps throughout the country, including in Badghis, Helmand, Nangarhar, Nuristan, and Zabul provinces. These training camps will allow al-Qaeda to rebuild its infrastructure and logistical networks, mobilize new recruits through its propaganda and ideology, and reconstitute an external operations capability to conduct transnational attacks. One member state suggested that longtime al-Qaeda veteran Saif al-Adel, believed to be the group’s de facto leader, has even relocated from Iran to Afghanistan. Al-Qaeda has been relying on donations from supporters, using both informal “hawala” networks and cryptocurrencies. The Taliban has also subsidized al-Qaeda, providing welfare payments that have filtered down to the group’s affiliates and branches.

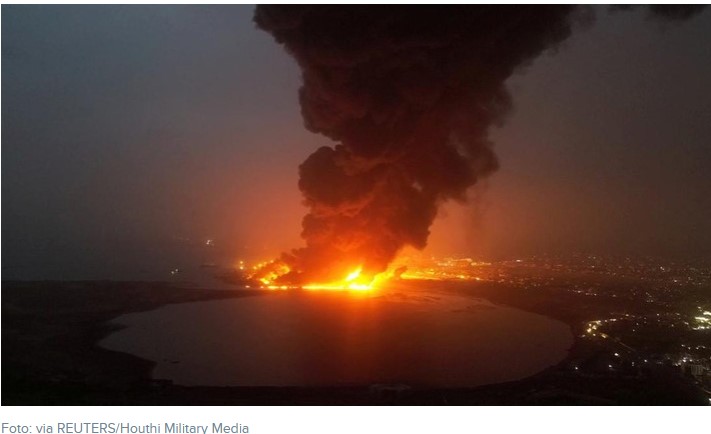

Islamic State Khorasan (ISK) is also a growing threat within Afghanistan, as its operations are becoming more sophisticated and more lethal. ISK presents itself as more hardline and austere than even the Taliban and has retained its sectarian agenda, which continues to be viewed as an effective recruiting tool and a focus of its propaganda. In 2022, ISK attacked high-profile foreign targets in Afghanistan, including Russian, Pakistani, and Chinese interests. According to the UN report, since last year, ISK has launched more than 190 suicide attacks resulting in over 1300 dead or injured. The group is in the process of transitioning from a hierarchically structured organization into a more networked one, and continues to operate training camps and develop sleeper cells that can be deployed for high-profile attacks around the country. Terrorist groups have more freedom of maneuver under the Taliban, and even those that the Taliban oppose, especially ISK, have been able to capitalize on the Taliban’s many counterterrorism missteps and governance deficits. While ISK will not be able to dethrone the Taliban, which remains qualitatively and quantitatively superior, the Taliban seems just as unlikely to fully extirpate ISK, leading to a situation of durable disorder and continued instability in Afghanistan, for which civilians are likely to pay the highest price, already facing crippling humanitarian crises and sweeping restrictions for women and girls.

In addition to al-Qaeda and ISK, there are a number of other terrorist groups active in Afghanistan, including Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), or the Pakistani Taliban, as well as the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU), Islamic Jihadi Group, Jamaat Ansarullah, and remnants of the East Turkestan Islamic Movement/Turkestan Islamic Party (TIP). Overall, UN member states reported that as many as twenty terrorist groups are currently operating in Afghanistan. These groups reportedly provide much-needed manpower to the Taliban and are occasionally enlisted to conduct attacks against the Taliban’s adversaries, including ISK, but also the National Resistance Front (NRF). The Afghan Taliban views the TTP as part of its broader emirate and has continued to work closely with the group. In training camps located throughout Afghanistan, al-Qaeda members have provided the TTP with training, especially in conducting suicide attacks. With no presence on the ground, the United States’ intelligence capabilities have atrophied, especially in terms of human intelligence (HUMINT), leaving Washington to tout its ‘over-the-horizon’ capability as an effective counterterrorism approach. But many in the counterterrorism community are far less sanguine. The situation is growing eerily reminiscent of the pre-9/11 period when terrorist threats metastasized in failed states and ungoverned regions were overlooked and assumed to be containable and not directly relevant to Western security interests (TSC)