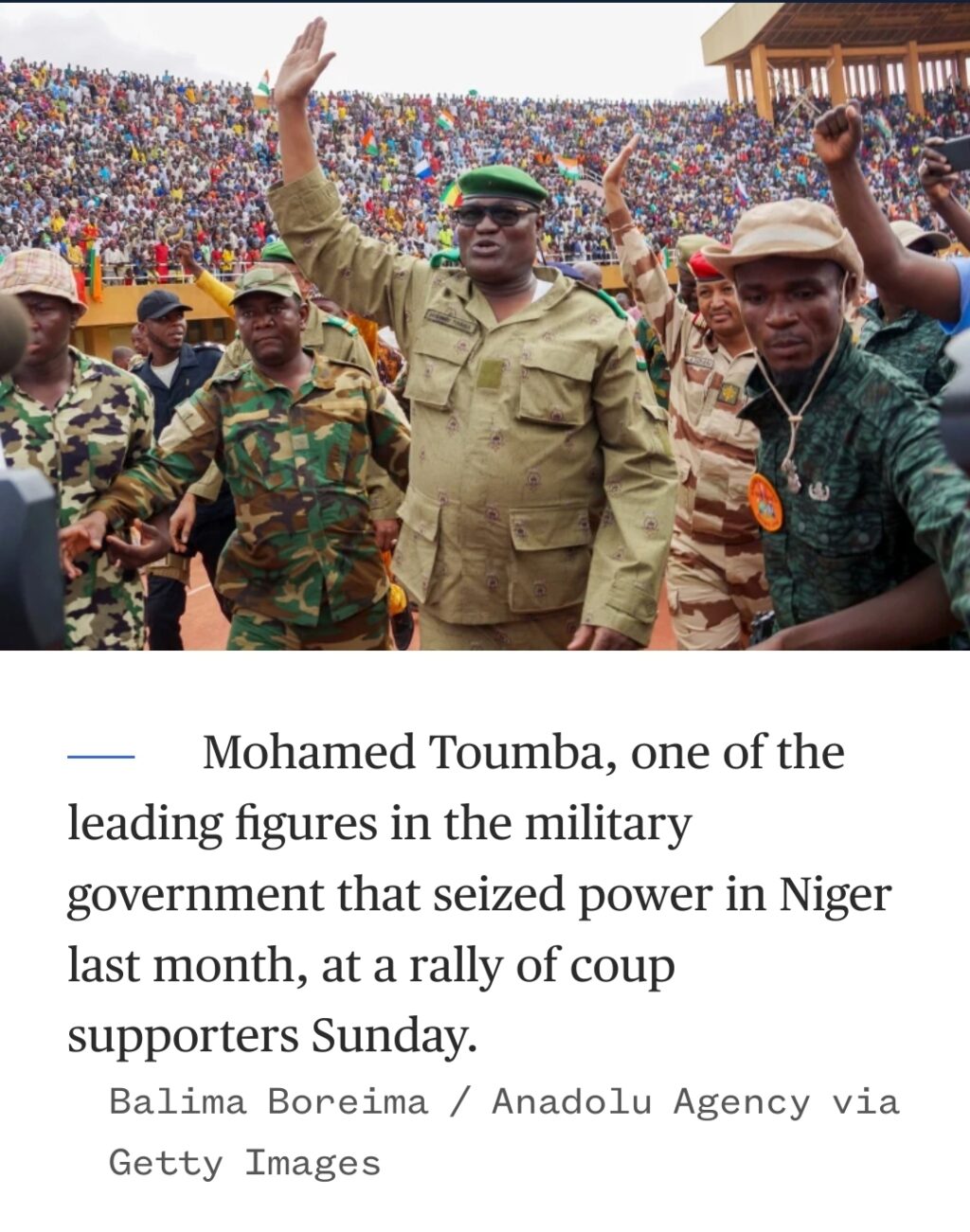

STRATEGIC ASSESSMENT, The recent coup in Niger is only the latest in a string of government upheavals across the increasingly unstable Sahel region after Nigerien military officers sequestered the democratically elected President Mohamed Bazoum. Many analysts have been unable to discern a tangible political objective behind the coup beyond maintaining access to resources and largesse for both the entrenched powerbrokers as well as an emerging new guard. The Wall Street Journal reports that prior to the coup, Bazoum had reduced financial benefits enjoyed by the presidential guard, led by General Abdourahamane Tchiani, who declared himself president of the transition council on June 28. Besides Tchiani, another leader of the coup – General Salifou Mody – was also an important figure in the previous establishment, having served as chief of staff for Niger’s armed forces before his appointment as ambassador to the United Arab Emirates in June. While Russia does not appear to have instigated the coup, it stands ready to capitalize on it, either through the Wagner Group or some other private military entity working at the behest of Moscow.

In comparison with Mali and Burkina Faso — countries where both Islamic State and al-Qaeda branches are active — Niger has been more successful in combating jihadist threats. Bazoum was outspoken about negotiating with jihadi factions active in his country, while at the same time publicly acknowledging the depth of Niger’s terrorism problem. He has admitted that “most of the Islamic State Sahel Province (ISSP) recruits were Nigerien nationals” from the Fulani community, that “arming civilians is a big mistake” – a juxtaposion with the policies of other Sahelian countries by opposing the arming of civilians to fight terrorist groups – and said that the region’s jihadist fighters were more experienced combatants than local armies and militias.

While Bazoum and his government officials collaborated with France, the United States, and other European and regional countries to combat Niger’s jihadist threat, Niger also purchased military equipment from Russia and Turkey, including Turkish drones. The Nigerien military has received training from the United States, France, Canada, Algeria, and Belgium. France remained active in support of the Nigerien army, with approximately one thousand to 1,500 military forces deployed mainly at Niamey’s airport and special forces deployed at another combat location. The United States maintains a similar force posture and controls the Agadez drone base. Italy and Germany are also invested in financing and training Nigerien forces, in addition to the European Union Capacity Building Mission in Niger.

In the past, Niger’s government has engaged in negotiations and de-confliction with groups like Jama’t Nusra’t al-Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM) the al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb’s (AQIM) Sahel branch while also carrying out traditional military operations against these groups. Bazoum’s willingness to engage in prisoner swaps and releases were cited by Niger’s junta to justify ousting him, although such actions are often employed while negotiating with jihadi factions in the Sahel. According to multiple sources, Islamic State recently secured the release of a prominent member of its organization in a deal with Malian forces that would reduce conflict with the state, allowing ISSP to focus on fighting its main adversary, JNIM. Islamic State forces throughout the Sahel are ramping up recruitment and could be on the cusp of taking over larger swaths of territory in the region.

Based on available data on terrorist attacks, one could argue that Bazoum’s policies were indeed making progress in reducing the jihadist threat to Niger, despite the justifications put forth by the newborn junta, which is constituted primarily of longtime Nigerien military officers. Individual demobilizations of jihadi fighters over the last three years in the Tillaberi and Diffa regions, following a model used to demobilize fighters of the northern Tuareg rebellion in the early-to-mid-1990s, had been producing positive results. This blueprint saw fighters rehabilitated and recruited into local “national guards” units. This process was facilitated by the High Authority for the Consolidation of Peace under the patronage of one of the coup leaders, former chief of staff General Mody.

On July 30, heads of state from the fifteen-member Economic Community of West African States threatened to take military action if the Nigerien coup leaders did not reinstate Bazoum within one week. The United States has also warned that it may halt its military assistance to Niger, while the European Union froze part of its aid to the country over the weekend. However, this could further open the door for Russian influence to enter the state and ultimately endanger coastal West African states – including Togo, Benin, Ghana, and the Ivory Coast – as violence continues to spread. The coup also threatens to undo Niger’s progress in its fight against jihadist groups. As a result, AQIM will likely enjoy greater freedom to maneuver in and out of Libya and potentially Sudan through Chad. Besides facilitating ISSP’s expansion, this could also create an open corridor with Islamic State West African Province (ISWAP), granting ISSP additional manpower, bombmaking expertise, and other logistical assets, which could shift the balance of power in the region towards Islamic State in its fight against al-Qaeda affiliates.

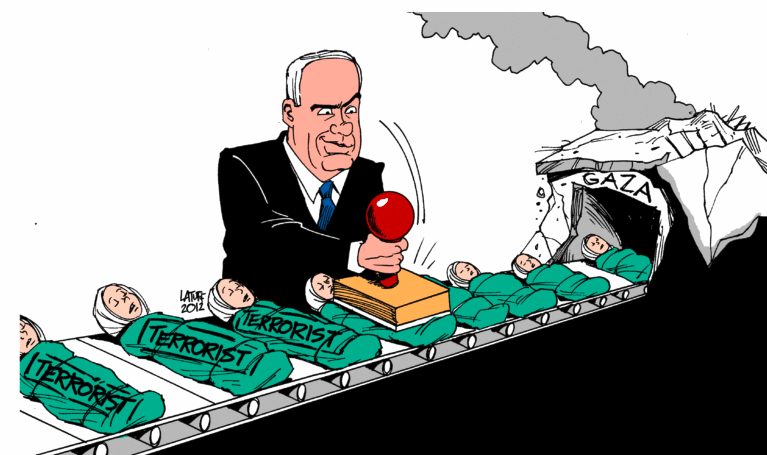

While jihadi factions battle for control of territory and resources across various parts of the continent, African military juntas are seeking to use counterterrorism as leverage to obtain popular support against the West as their predecessors used to get economic and diplomatic support from the West. Western governments’ militarized approaches to countering global terrorist activities over the past two decades has empowered the same military leaders who are now spurning Washington and turning toward Moscow – not only in Niger, but in several other African states as well. Meanwhile, these warlords act in a rapacious manner, enriching themselves while further exacerbating the grievances of the local population, pushing them closer to jihadists groups or other violent non-state actors. After an approach that almost over-relied on military force and its subsequent reversal – as the West now that they appears unwilling to continue intervening in Sahelian countries – Western countries may appear weak on the ground in these same states where they may have previously been decried as colonizing or oppressive forces. Longstanding Western-led capacity-building programs and the billions of dollars dedicated to development, education, and human rights issues are likely to be challenged by Russian disinformation campaigns and the populist agitation of locals in crowded urban areas. Paris and Washington will pay a high political price and bleed influence if they cannot adapt to the current state of play in the Sahel, where negotiation with rogue actors and the muscular demonstration of military power remains a viable option. Otherwise, the Sahel should be abandoned to those who are willing and able to play such a difficult option (TSC).