Logo Sinn Fein-Wikipedia

STRATEGIC ASSESSMENT. Sinn Fein, the Northern Irish political party that initially emerged as the political wing of the Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA), won big in this weekend’s U.K. elections, making it the dominant party in the Northern Ireland Assembly. The results are historic for many reasons, but above all else, it marks the first time that a nationalist party has ever won the most first choice votes. Unionist parties have led the legislature since 1921, when Northern Ireland emerged from the ashes of the Irish War of Independence (1919 – 1921). Sinn Fein’s victory also demonstrates that political parties can emerge from terrorist groups and ultimately go on to favor the ballot over the bullet and do so successfully. Sinn Fein is also a dominant political party in the Republic of Ireland. Pro-U.K. Unionist parties lost popularity following Brexit, the highly controversial vote which finalized Britain’s divorce from the European Union, opening the door for Sinn Fein to gain more power. South of the border, Sinn Fein has capitalized on Ireland’s faltering economy, campaigning on housing and inequality, hot button issues that have resonated with Ireland’s electorate.

Last weekend’s elections could mark a major shift in regional political dynamics. Sinn Fein’s win has implications beyond Ireland and Northern Ireland, signaling a setback for the U.K.’s Conservative government. The once dominant pro-U.K. Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), which campaigned strongly against the Northern Ireland Protocol, came in second, while the Alliance Party, which transcends the typical Catholic-Protestant divide in Northern Ireland, came in third, establishing itself as a legitimate political force for the first time. Under the post-Brexit terms of the Northern Ireland Protocol, there are new customs and border checks on some goods entering Northern Ireland from other parts of the U.K., threatening the free flow of trade, a centerpiece of the Good Friday Agreement and fundamental to the success of the peace process. Sinn Fein, for its part, has kept any talk of unification on the back burner, downplaying the prospect in favor of traditional “bread and butter” issues, including the economy, inflation, and skyrocketing costs of living.

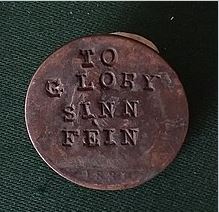

In many quarters of Northern Ireland, the Republic of Ireland, the United Kingdom, and Europe, there are significant implications for the future, including the possibility that Sinn Fein will agitate for a united Ireland, long the stated objective of both Sinn Fein and the PIRA, sometimes referred to as the “Provos.” PIRA propaganda has featured slogans such as “26 + 6,” which referred to the 26 counties in the Republic of Ireland, combined with the 6 counties of Northern Ireland, which maintains a Protestant majority and a political landscape dominated by Unionists and Loyalists that look not to Dublin, but to London and Stormont (the seat of Northern Ireland’s parliament). Sinn Fein is historically comprised of Irish Republicans and Nationalists, who have been in favor of a united Ireland, north and south. If Irish unity once again becomes a major platform, it could lead to an uptick in sectarian violence between Catholics and Protestants in Northern Ireland, just one year shy of the twenty-five-year anniversary of the landmark Good Friday Agreement (also known as the Belfast Agreement) of 1998, which officially ended the three decade-long conflict colloquially referred to as “The Troubles.”

Sinn Fein’s rise to prominence is somewhat of a double-edged sword. On the one hand, it demonstrates to other active terrorist and insurgent groups that it is possible for once violent organizations to make a thorough transition to politics. Groups like Hamas, Hezbollah, FARC and other so-called hybrid groupshave in some ways modeled their actions on the PIRA and Sinn Fein. On the other hand, Sinn Fein’s victory will inevitably open old wounds, potentially destabilizing Northern Ireland in the process. The question of a united Ireland reinvigorates the PIRA’s raison d’etre and highlights its ethno-nationalist objectives. It remains to be seen whether hardline Unionists would agree to sit in a government in which Sinn Fein holds the post of first minister in the Northern Irish parliament. If the government breaks down, it will lead to further paralysis and dysfunction, potentially increasing the likelihood of conflict. Beyond Northern Ireland, there are concerns throughout the U.K. that a push for a united Ireland could accelerate Scotland’s independence movement, a scenario that many anti-Brexit campaigners presciently warned about in the lead up to that vote (TSC).