STRATEGIC ASSESSMENT-The Russia-Ukraine conflict isn’t just about the clash of armed forces on the battlefield. It has also been marked by unprecedented levels of confrontation in the fields of information and psychology, cognition and semantics.

Kiev has arguably achieved more success on the information front, than on the ground. There the “fighters” aren’t just journalists and information and psychological warfare specialists, but content makers and PR experts. Influencing the psyche, mindset, and emotions of ordinary people has become a big deal, as shaping Western public opinion is vital for President Vladimir Zelensky’s regime.

The symbols of war

Anyone familiar with advertising and PR knows that tying an product to a colorful, memorable symbol, or slogan, will boost its popularity, especially in this era of short attention spans. During wartime, the same strategy works just as well with the news as with advertising and election campaigns.

In the current conflict, Ukraine has become very good at creating symbols. Media outlets instantly take up any popular symbol and make use of it in order to influence the mindset of ordinary Ukrainians.

Here’s a recent example. In May, despite the very difficult situation for the Armed Forces of Ukraine (AFU) in Artemovsk (Bakhmut) and statements from several commentators – particularly the former Zelensky adviser Alexey Arestovich – that the army could soon retreat (as it eventually did), Ukrainian society wasn’t at all worried and had complete faith in the AFU’s ability to retain control over the city.

In fact, public attitudes towards the battle were largely shaped by the media. For example, at the beginning of the year the rock band “Antytila” (“Antibodies”) released a video for the song ‘Bakhmut Fortress.’ A few months later, it became viral. Ukrainians have since posted countless self-made versions of the video on social networks, affirming the myth of the impenetrable fortress of Bakhmut.

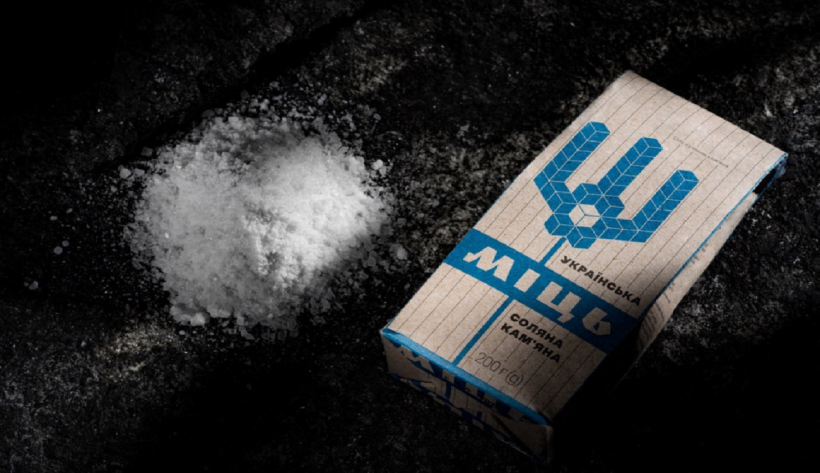

Such symbols are created not only during ongoing battles, but also in the aftermath of the AFU’s obvious failures. For example, at the end of February, the Artemsol salt production enterprise announced that before the start of active battles for Soledar (which ended in January with the victory of the Russian Army), it collected 20 tons of salt from the mines. The salt was packed into 100,000 packages bearing the symbolic inscription “Ukrainian Rock-Solid Strength.” Each package was sold for 500 hryvnia (about $13.50). According to the organizers of the fundraiser, most proceeds were spent on kamikaze drones for the AFU.

Symbolic campaigns like these occur regularly in Ukraine and are designed to encourage the population. In November of last year, when Russian troops withdrew from the west bank of the Kherson region and the AFU entered the eponymous regional capital, a national social media campaign urged users to place images of watermelons (the area grows them) on their profile pictures.

Kherson has been known for many things in its history – such as shipbuilding in the times of the Russian Empire and the USSR. However, for some reason, Ukraine’s propaganda decided to associate it solely with watermelons, and the imagery was well-received by society. In a state of victorious euphoria, people forgot about the regular blackouts and ongoing fighting in the region.

The detection dog Patron [Ukrainian for “cartridge”] became another famous Ukrainian symbol. It helped Chernigov engineers clear the territories of mines. In addition to media exposure, Patron was even granted a meeting with Zelensky. Posters with a picture of the dog explained how to act if you detect an explosive object and can still be seen around Kiev and other cities. A toy version of Patron even appeared on the shelves of children’s stores, along with miniature models of [Soviet-designed] Mriya aircraft, [Turkish] Bayraktar drones, and [American] HIMARS vehicles.

Postage stamps – issued by Ukrposhta, Ukraine’s state postal service – have become another tool. While Zelensky claims that Ukraine was not involved in last month’s drone attack on the Kremlin, Ukraine decided to issue a stamp showing this very attack. The head of Ukrposhta, Igor Smelyansky, commented that new stamps are often a forerunner of “positive events.”

In more than a year of hostilities, Kiev’s use of symbols and memes to raise or maintain morale and help control the narrative has been streamlined to a surprising extent. Google’s ranking of top Ukrainian search queries in 2022 is more proof. For example, in the “person” category, Ukrainians most often Googled “Alexey Arestovich” and showed interest in the “ghost of Kiev,” a legend of a supposed hero pilot which The Wall Street Journal admitted was fake military propaganda intended to raise morale. In the “purchase of the year” category, the postage stamp “Russian Ship” was among the most popular search queries. This was a stamp issued in honor of the soldiers on Snake Island who, as the fake story went, responded in abusive language to an offer from a Russian ship’s crew to surrender and fought to the death. These border guards were “posthumously” awarded the Hero of Ukraine decoration but later it was revealed that all of them had voluntarily surrendered and were alive.

The triumph of these symbols, which have endured long after being confirmed as fake, is a result of the information bubble in which Ukrainian society and much of the West has found itself. In the past year and a half since opposition media was blocked, government-controlled outlets are often the only source of information for Ukrainians.

The invisible front

“Today, information warfare is the core structure of any war. It is very important to have influence over a society that is involved in combat. Moreover, it is essential to convince the world community of the rightness of our actions in order to receive further support. Not only authorized persons can take part in this information war, but also regular citizens who ‘fight’ at their own discretion,” Ukraine’s Deputy Defense Minister Anna Maliar said in February.

Information and Psychological Operations (IPsO) are intended to brainwash people and shape public opinion, and they are among Kiev’s most important strategies in the conflict with Russia. In combat conditions, these operations are primarily aimed at demoralizing and disorganizing the enemy’s front and rear and inspiring a hopeless, doomed atmosphere. Usually, their main task is to discredit the military and political command and highlight defeat and failure.

In December 2019, a network of IPsO centers with access to internal and external mass media and internet resources was deployed in Ukraine. In the AFU, information and psychological operations fall under the jurisdiction of Special Operations Forces. This means that their work and personnel are kept top secret. However, some information has recently been revealed.

At the state level, the coordination and general management of cybersecurity and information operations is carried out by the National Security and Defense Council of Ukraine (NSDC). The National Cybersecurity Coordination Center of Ukraine was established in June 2016 as a working body of the NSDC. The outfit includes the heads of ten government departments, such as the Security Service of Ukraine, the Ministry of Defense of Ukraine, and the Main Directorate of Intelligence.

Cyber operations and information campaigns are directly implemented by the special IPsO centers which are part of the Special Operations Forces of the AFU. Currently, there are four such centers: the 16th center (military unit A1182, Guiva, Zhytomyr Region), the 72nd center (military unit A4398, Brovary, Kiev Region), the 74th center (military unit A1277, Lviv), and the 83rd center (military unit A2455, Odessa).

In addition to counterintelligence activities, they organize propaganda campaigns on the internet and television, create and publish fake information, and, together with the SBU, coordinate the activities of hacker groups, volunteer information communities, and other internet resources. Before active hostilities, the centers were estimated to employ around 500-550 people, while some sources claim they had over 1,000.

These units act independently and collaborate with similar foreign structures. Foreign centers and information troops give them access to large commercial resources. Activists and celebrities are also involved in the process. “Since February 24, we have all become soldiers on the information front,” said Vadim Miskyi, Program Director of Detector Media.

The Ukrainian Cyber Alliance has also operated in the country since 2016. This is a community of cyberactivists from different Ukrainian cities and from abroad. The community conducts cyberattacks, and hacks web pages and emails.

In February 2020, the special Command of the Communications and Cyber Security Forces was formed as part of the ongoing reform and structural reorganization of the AFU to match NATO standards. The plan was to create units identical to NATO’s cyber centers. Specialized centers also exist in other Ukrainian state departments including the Security Service of Ukraine and the Ministry of Internal Affairs to the State Cyber Protection Center.

As part of Ukraine’s integration into NATO structures, special unit instructors from the United States and other Western countries are involved in the training of IPsO center personnel. In particular, these are specialists from the US Army’s 4th Psychological Operations Group (formerly called the 4th Military Information Support Group) and the UK’s 77th Brigade – a special unit of information, psychological, and cyber operations of the Armed Forces of Great Britain. IPsO specialists also undergo regular training at US military bases.

Disinformation and propaganda

In addition to official media outlets, Ukraine’s Information and Psychological Operations Centers rely on several thousand internet resources including information and news sites, social networks, and coordinated social media groups.

Even before the start of Russia’s military campaign, certain Ukrainian volunteer internet information resources were controlled by IPsO centers. This included the volunteer communities InformNapalm, (informnapalm.org ), Peacemaker (psb4ukr.org ), Information Resistance (sprotyv.info ), as well as commercial sites (seebreeze.org.ua, petrimazepa.com, podvodka.info, metelyk.org, mfaua.org, burkonews.info, euromaidanpress.com , peopleproject.com and others) used for information campaigns and testing “social engineering” technologies. In particular, it was noted that IPsO officers often operated under the guise of “volunteers” and pseudo-bloggers.

Ukrainian officers, soldiers, and volunteers are taught the art of information and psychological operations based on leading world standards. In an interview, Arestovich quoted US textbooks on information warfare. “Do you know how information and psychological combat works? The first page of the US textbook on information and psychological warfare, the first chapter, says – I quote: the main task of information and psychological operations is to take over the agenda. That’s it, after that you can just relax and do nothing.”

Ukraine uses various tools – including websites, social networks, and bots – to spread disinformation. In April, hackers from RaHDit and other groups revealed Ukrainian Telegram channels presumably supervised by the SBU, which posed as pro-Russian. An entire network of such channels, with an audience of 5-6 million people, was discovered during the investigation. The list includes channels Operation Z, Novorossiya 2.0, and many others.

Hackers note that most of these channels previously had radically different content before they were taken over. They also hosted fake fundraisers for the needs of the Russian Armed Forces. Most of the administrators were Ukrainian citizens and one of the key players was Luka Ilchuk, who is responsible for many of the fake channels.

How did these channels work? Quite simply: the pseudo-patriotic channels published ordinary news posts, were gradually promoted to reach a bigger audience, and then the Ukrainians threw in their own narrative between the lines. For example, there was a story about an investigation concerning PMC Wagner fighters who allegedly shot large numbers of civilians in Artyomovsk (Bakhmut). In other words, the channels were designed to sow panic, create outrage, and spread disinformation.

Psychological warfare expert Paul Linebarger believed that war always begins long before the start of combat and continues for some time after it ceases. Unlike traditional warfare, where the battle is between two armies, psychological warfare is waged against millions of civilians who have little ability to fight back.

Today, the information war is indeed one of the major factors influencing the overall conflict and the situation at the front line. Modern battles are won not only with weapons, but with public support. Kiev understands this well. After all, much depends on how this conflict is perceived inside and outside Ukraine.