STRATEGIC ASSESSMENT-Naypidaw. The state news outlet Global News Light of Myanmar said that the accusations meant the men “gave directives, made arrangements and committed conspiracies for brutal and inhumane terror acts.” This appears to be the first use of capital punishment in decades though since seizing power the junta has not hesitated to violently suppress opposition leaders, protesting civilians, or minority groups like the Rohingya. United States Secretary of State Antony Blinken has condemned the executions, saying, “Such reprehensible acts of violence and repression cannot be tolerated. We remain committed to the people of Burma and their efforts to restore Burma’s path to democracy.” Malaysia called the executions a crime against humanity and the Association of South-East Asian Nations (ASEAN) called them “reprehensible,” while Cambodia also denounced the killings. The U.S. State Department reiterated that there could be no “business as usual” with the junta and has called on China to exert more political pressure, though the regime in Naypyidaw challenged these criticisms with a defiant defense, perhaps emboldened by the relative lack of pressure it has faced from influential regional neighbors.

Recently, soldiers from the military in Myanmar, known as the Tatmadaw, confessed to killing, torturing, and raping civilians in an exclusive interview with the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC). There have been horrific accounts of the deliberate violence, they were ordered to perpetrate, including shooting civilians, burning entire homes and villages, sometimes with people in them, and raping women and girls to deter any support for the People’s Defense Force (PDF), a group of civilian militia groups fighting for a democratic transition. The BBC interviews recount a systematic and deliberate campaign of violence waged by the military, reflecting a culture of impunity enjoyed for decades. Last year, protesters decried the military coup, which ousted the democratically elected leader, Aung San Suu Kyi,x who has been detained since February 2021 and has been sentenced to more than a decade in prison on charges that Human Rights Watch has referred to as “bogus.” More than 1000 civilians have reportedly been killed since the coup, with the junta asserting that those who were killed or detained were “terrorists,” which bodes ill for those still in detention.

The junta in Myanmar has also used the premise of fighting terrorism or militants as a rationale for its latest violent crackdown on the Rohingya community in Rakhine state. Medecins Sans Frontieres reported that at least 6,700 Rohingya, including at least 730 children under the age of five, were killed in just the first month after violence broke out in August 2017. Since then, there have been widespread reports of systematic burning of villages, torture, and rape. The U.N. estimates that over a million Rohingya refugees have fled to neighboring Bangladesh since the 1990s, greatly stretching the capacities of the host nation and local communities in Chittagong and Cox’s Bazar. The Rohingya have been denied citizenship in their home state and the United Nations estimates that they are the world’s largest stateless population; in March 2022, Secretary Blinken labeled the crisis a genocide and affirmed that the campaign against the Rohingya fit the definition of that gravest of crimes.

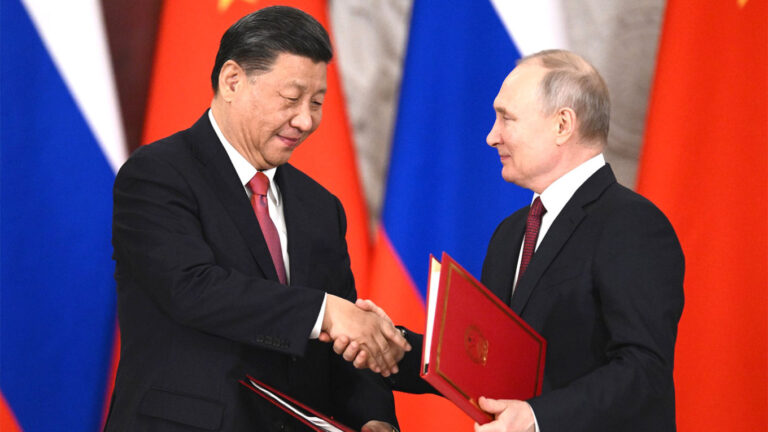

Despite the scale of the violence visited by the junta on the people of Myanmar, the international community has done little to hold the junta accountable. In large part, this is due to China’s reluctance to pressure the junta over the atrocities. Instead, China has chosen to protect Myanmar from censure and sanctions in the United Nations Security Council, despite the efforts of several states to shine a light on the issue and hold Myanmar to account. The recent Press Statement from the Security Council could be read as an indication of some level of consensus between the members, but pales in comparison to the scale of violence perpetrated by the military. In October 2021 Myanmar pledged to abide by a regional peace plan developed by the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and backed by the U.S. and China, but regional neighbors have asserted that recent events have made a “mockery” of the plan. China cites its “non-interference” policy, which stipulates that states must not intervene in one another’s internal affairs, for its unwillingness to condemn the executions. Beijing invokes this same defense to fend off criticisms of Chinese persecution of dissidents and its Uyghur population. Earlier this month, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s trip to Myanmar was criticized for undermining ASEAN unity, and while it remains unclear if it emboldened the junta to carry out the executions, it certainly did not deter them.

While the international community has struggled to resolve the crisis in Myanmar, a small state has had an outsized impact in addressing the ongoing genocide. In November 2019, The Gambia, brought Myanmar to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) over alleged violations of the Genocide Convention against the ethnic Rohingya population. In early July, the ICJ rejected Myanmar’s jurisdictional objections, paving the way for The Gambia v. Myanmar to go forward. In a press release, The Gambia’s Ministry of Justice welcomed the decision and reaffirmed its commitment to pursuing justice and accountability at home and abroad, and its pride in leading the international effort to address the Rohingya genocide. The landmark case highlights that while great power competition and regional dynamics have failed so far to deter the junta in Myanmar and stem the violence, there are other avenues available to pursue accountability.