STRATEGIC ASSESSMENT. U.S. sanctions against the Taliban movement in Afghanistan have been in place, although with periodic modifications, since the 1996-2001 period of Taliban rule. U.S. sanctions imposed during that period were intended to pressure the movement to expel al-Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden and to end abuses against Afghan women and minorities. In July 2002, following the U.S.-led war that decimated al-Qaeda and ousted the Taliban from power, then President George W. Bush eased U.S. sanctions to empower and assist the post-Taliban, U.S.-backed government. However, in order to maintain economic and diplomatic pressure on the Taliban in its altered role as an outcast insurgent group, President Bush designated the Taliban as a terrorist group under Executive Order 13224 (of September 2001). Successive administrations kept maintained that designation to continue countering the Taliban insurgency. In 2012, in recognition of its involvement in bombings that killed Afghan civilians and kidnapping of Westerners, President Obama named the Haqqani Network, a group centered on the Haqqani family and functioning as part of the Taliban, as a Foreign Terrorist Organization (FTO). The designation was made pursuant to legislation requiring the Administration to formally report to Congress whether that network qualified for such a designation. The United Nations also has in place a list of sanctions on Taliban leaders, though this was separate from the counterterrorism sanctions regime under Security Council Resolution (UNSCR) 1267 in 2011 to incentivize negotiations with the Taliban; the sanctions list and measures themselves remain in place under a new regime guided by UNSCR 1988.

The Taliban’s return to power in Afghanistan in August 2021, and its appointment of Haqqani Network leaders to key government positions, has highlighted the sanctions issue as the international community attempts to mitigate the effects of the political transition on the vulnerable Afghan population. The Afghan economy, including the private sector, benefitted from extensive development spending by the U.S. and its allies during 2001-2021, support that has ceased following the Taliban’s August takeover. The U.S. response also included freezing nearly $9.5 billion in Afghanistan’s central bank assets, which amounts to roughly one-third of the country’s annual economic output, rendering the Afghan population completely dependent on international assistance.

U.S. and UN terrorist designations do not carry a humanitarian exception—an exception that is routinely embedded within most other U.S. sanctions laws and executive orders. Recognizing that humanitarian aid is crucial in light of the Afghan economy’s collapse, on September 24, the Biden administration issued two “general licenses” (GL 14 and GL 15) to blunt the effect of the sanctions without fundamentally changing the U.S. sanctions posture. The licenses act as blanket permission for international organizations to provide humanitarian aid to the Afghan people and companies to export certain goods to the country. According to the Treasury Department announcement, the “two general licenses (GLs) [were issued today] to support the continued flow of humanitarian assistance to the people of Afghanistan and other activities that support basic human needs in Afghanistan…Treasury will continue to work with financial institutions, international organizations, and the nongovernmental organization (NGO) community to ease the flow of critical resources, like agricultural goods, medicine, and other essential supplies, to people in need, while upholding and enforcing our sanctions against the Taliban, the Haqqani Network, and other sanctioned entities.”

Still, a 2019 executive order added a penalty to Executive Order 13224—barring the U.S. financial system to foreign bank that conducts financial transactions with a designated terrorism entity. Global banks are traditionally cautious, and the Taliban’s designation means that global banks will likely refuse to provide letters of credit (financing) for any commercial trade with Afghanistan—including trade with Afghan companies without any links whatsoever to the Taliban. Under binding Security Council resolutions 1267 and 1373, and subsequent iterations, states are also obliged to enact a number of measures to counter the financing and support for terrorism; none of these contain a humanitarian exception or a licensing mechanism allowing for the protection of legitimate humanitarian activity in conflict zones where terrorist groups operate. Forthcoming negotiations on renewing the mandates for the two expert bodies charged with supporting implementation of these resolutions, the Counter-Terrorism Executive Directorate (CTED) and the Al-Qaeda/ISIL Monitoring Team and sanctions regime, are unlikely to alter this scenario despite several states’ interest in doing so.

A return of Afghanistan to normal global commerce, and particularly trade with U.S. companies, will therefore require a revocation of the terrorism designations that currently apply to the Taliban and the Haqqani Network. But, any Biden administration decision to “de-list” those movements will hinge on whether the Taliban upholds its pledge to the U.S. to deny Afghanistan safe haven to global jihadist groups, and need to be complemented by international action. In addition, many argue that no sanctions should be eased unless the new government also adheres to international standards of human rights, including for women. The Taliban’s reported continued relationship with al-Qaeda, and its early moves to limit girls’ access to higher education and work in government, do not portend an early easing of U.S. sanctions.

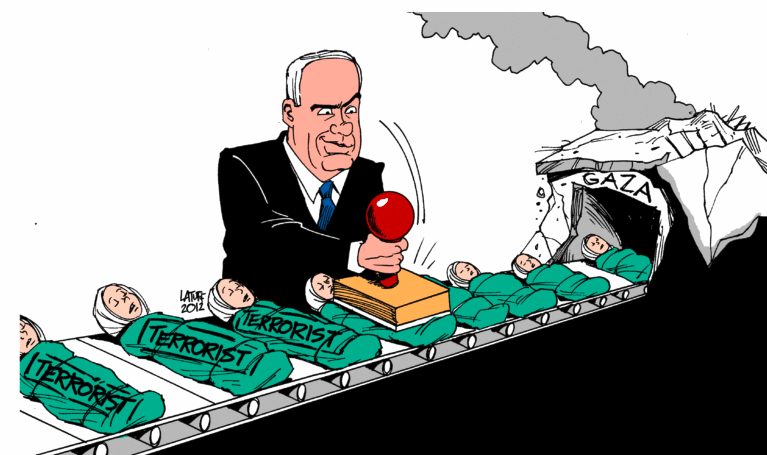

The effect of sanctions on Taliban-ruled Afghanistan raises broader questions about how sanctions regimes intersect with the humanitarian needs of populations ruled by movements and factions that are accused of involvement in terrorism. As has been the case in Afghanistan, exceptions have had to be issued to enable the delivery of humanitarian aid to the population of Gaza, which is run by the U.S.-designated FTO Hamas, and to areas of Yemen controlled by the Houthi movement, which was designated as an FTO in the final week of the Trump administration (and de-listed by the Biden administration in February 2021). The UN has developed an exceptions mechanism in North Korea and Somalia, the latter of which is a unique case where the U.S. has pushed to keep Al-Shabab off the “1267” terrorism sanctions list in order to allow for the delivery of international humanitarian assistance. Sanctions have worsened the economic crisis in Lebanon because of the preponderant influence there of U.S.-designated FTO Lebanese Hezbollah. The difficulties that U.S. sanctions create for vulnerable populations governed by designated terrorist groups might argue for developing new strategies for designing and implementing precisely targeted U.S. sanctions policies. Humanitarian actors and civil society groups have long voiced concerns about the risks and punitive measures they face in areas where terrorist groups operate—from Somalia to Afghanistan—which also include preemptive measures taken by banks, such as derisking, and burdensome donor clauses that risk compromising and overstretching many NGOs. Over twenty years after these measures were put in place, it’s time to consider how to ensure robust counterterrorism responses while also allowing for legitimate humanitarian assistance and civil society engagement (TSC).