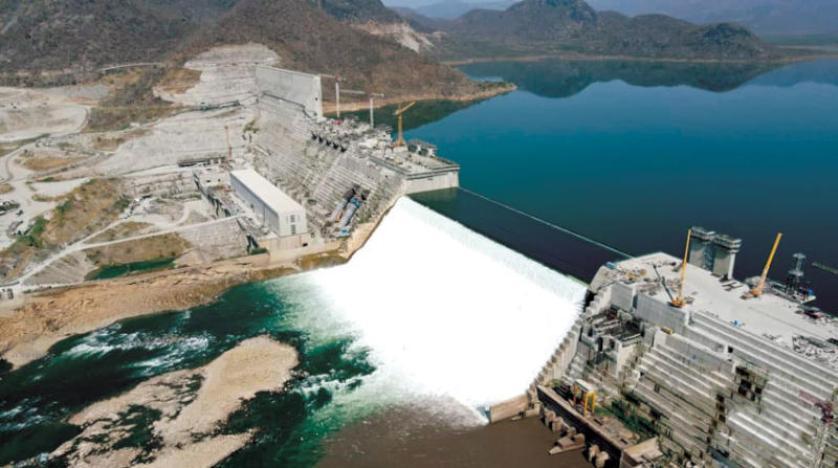

The photo has taken from Asharq Al awsat

STRATEGIC ASSESSMENT. Tensions have continued to destabilize northeastern Africa over Ethiopia’s insistence that it has the legal right to build the Grand Ethopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) on the Nile River. The project, if successfully completed, would provide Ethiopia with approximately sixty percent of the country’s power needs. However, Ethiopia’s northern neighbor, Sudan, has assumed a hostile approach toward the project. Sudan’s position represents something of an about face. After undergoing a popular revolution in 2019 to overthrow its longtime brutal dictator, Omar al-Bashir, Sudan’s new government has increasingly opposed the construction of the dam.

Sudan’s military retains significant influence over the transitional government in Khartoum, especially with respect to foreign and security policy. The transitional government leader, Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, has been chiefly responsible for normalizing, or what he termed “reconciling,” Sudan’s relations with Israel even while civilian political leaders opposed the deal. Nevertheless, just as economics were central to Burhan’s warming up to Israel, which led to the U.S. dropping Sudan from its “state sponsors of terrorism” list and opened investment opportunities, economics also forms part of Sudan’s opposition to the GERD. Construction of the dam, located along the Blue Nile in Ethiopia’s Benishangul-Gumuz region could threaten the water supply of both Sudan and Egypt, and risks increased flooding in Sudan.

Egypt, Sudan’s powerful neighbor to the north, favors a more aggressive stance toward Ethiopia on the GERD. During Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi’s March visit to Khartoum, al-Sisi seems to have offered Sudan support for its small-scale invasion of Ethiopia weeks earlier on the condition that Sudan maintained pressure on Ethiopia over construction of the dam. Shortly after Ethiopia launched operations to quash an uprising by rebel military officers in Tigray in November 2020, Sudanese troops amassed near al-Fashaga, disputed territory Ethiopia has claimed as its own since the mid-1990s and is now settled by Ethiopian farmers. By March 2021, Sudan advanced its forces deep into al-Fashaga but insisted the troops remained in “Sudanese territory” and did not disturb Ethiopian farmers. Sudan also alleged Eritrean troops, which were allied with Ethiopia against the Tigrayan rebel commanders, were in al-Fashaga. However, without further evidence of this, Sudan may have made this allegation merely as a pretext to justify its incursion.

Although Ethiopia asserted it did not wish to fight Sudan over al-Fashaga and sought a return to the post-2008 status quo arrangement where Ethiopian troops were free to maneuver in the area, Ethiopia did imply Egypt was behind the Sudanese incursion. In turn, Ethiopia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokesperson stated that a “third party” was behind Sudan’s actions; the implication being that Cairo is using al-Fashaga as a bargaining chip in its negotiations with Addis Ababa over the GERD, with Khartoum functioning as Egypt’s proxy. A worst-case scenario would involve Egypt’s air force bombing the GERD and destroying the project altogether. This would inflame regional tensions and could lead to a war between Egypt and Ethiopia that would draw in other regional and international powers. Sudan would likely ally with Egypt and use al-Fashaga as a staging point for incursions deeper into Ethiopia in such a scenario. Nevertheless, any potential Egyptian airstrike on the GERD appears to be a much more drastic action than current trends suggest.

There are also regional attempts at negotiation over the GERD. The United Arab Emirates, which maintains close relations with Egypt, Sudan, and Ethiopia, has agreed to mediate between Egypt and Ethiopia. Although Sudan and Ethiopia consented to mediation, Egypt refused. Details about the UAE’s proposal have not been made widely available. President Al-Sisi nevertheless discussed the GERD with Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan during a recent meeting in Abu Dhabi. Thus, Egypt may be open to some form of Emirati mediation once al-Sisi receives more confirmation from the UAE on what its proposal will entail.

It is still premature to expect disagreements over the GERD to lead to war, especially since Ethiopia is militarily focused on Tigray and has not responded with force to Sudanese troops’ presence in al-Fashaga. Moreover, there is still time for a negotiated agreement since GERD is not expected to be fully operational until at least 2023. The Biden administration could also seek to play a more active role in any mediation, but thus far, the administration is “reviewing” the GERD. The Administration also indicated that it may still provide economic aid to Ethiopia even while Ethiopia moves forward on the dam project. Whatever decision the Biden administration takes on the GERD will impact U.S. relations with Egypt, which in turn affects U.S. broader policy in the Middle East. These tense regional dynamics also highlight the specter of future “water wars” or conflict driven by climate change and increasingly scarce resources. Many of the grievances related to underdevelopment, inequality, and poor governance create an enabling environment for terrorist groups to recruit (TSC).