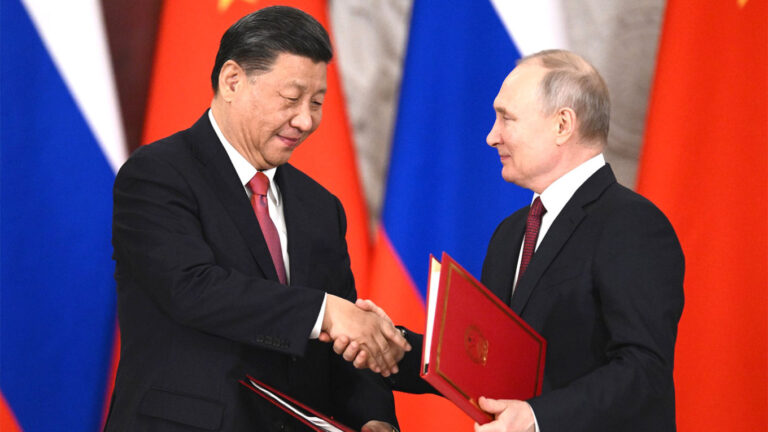

STRATEGIC ASSESSMENT. The alignment between the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and the Russian Federation has increased under Xi Jinping’s and Vladimir Putin’s leadership, respectively. In 2022, just days before Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Xi and Putin announced a “no limits” partnership between the two countries — spanning economic, communication, military, sanction circumvention, and energy cooperation. A burgeoning part of the cooperation between Beijing and Moscow appears to occur in Internet censorship and disinformation campaigns, where each learns from the other’s tactics, techniques, and procedures to suit their own independent strategies and goals. Beginning in 2017, representatives from China and Russia’s chief Internet regulators, the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) and Roskomnadzor, held several meetings where they compared notes on issues related to Internet control and regulation, as well as “foreign-produced” harmful content and how to use the Internet to “form a positive image,” both domestically and internationally. Recent years have illustrated how Russia has more forcefully and successfully deployed Internet censorship tactics that China has historically used. At the same time, Beijing has taken a page from Russia’s disinformation playbook and applied it to its goals of shaping the global information environment favorably for China.

Russia’s Internet censorship and regulation methods and tactics have evolved over the past decade to more closely simulate aspects of China’s notorious “Great Fire Wall.” A decade ago, Russia deployed a fairly open-access approach that instead utilized disinformation and propaganda on sensitive issues aimed at its population to stoke mistrust and confusion and drive people to seek information from state-run media and information sources. Following the 2018 Russian presidential election, which saw a victory for Putin, unsurprisingly, laws and tactics aimed at tighter Internet control became more widespread, with the government banning some websites and applications, threatening legal action against independent bloggers and journalists, passing restrictions on virtual private networks (VPNs), and often slowing Internet traffic to the point where access to what was deemed “sensitive” or “harmful” information became virtually impossible. In meetings dating back years, Russian officials specifically sought practical advice from their Chinese counterparts on disrupting VPNs and cracking down on encrypted Internet traffic and messaging platforms. It appears some of that know-how has now been applied in Russia. In 2019, the controversial “sovereign Internet” law came into effect, allowing the Kremlin to exert more control over the Internet — specifically by routing web traffic through state-controlled infrastructure. Since Putin launched the 2022 war on Ukraine, Russian laws and implementation of Internet regulation have become even more restrictive and technically sophisticated, closely resembling some of China’s methods. In the past two years, and especially in light of Alexei Navalny’s death and the recent Russian presidential election, Moscow has disrupted VPNs and even blocked access to messaging apps like Telegram across a whole region in moments of political instability or for fear of protests — illustrating technical sophistication and close cooperation with Internet and telecommunications providers in the country.

At the same time, the PRC appears to have closely studied the Russian disinformation playbook and adopted specific tactics, techniques, and procedures to suit its goals of denigrating the United States and shaping the global information environment in Beijing’s favor. Since 2020, the PRC has shifted some of its disinformation campaigns targeting citizens in other countries from focusing exclusively on positive messaging about Beijing to deploying more insidious narratives and conspiracy theories to stoke confusion and mistrust. During the Hawaii wildfires last year, a large-scale, likely PRC-backed/aligned network on social media was pushing conspiracy theories aimed at accusing the U.S. Department of Defense of causing the fires due to testing of a “secret” weapons system. The disinformation campaign, which spanned several social media platforms, also employed AI-generated imagery. Beijing has also amplified Russian-seeded disinformation narratives, for example, related to allegations of U.S. “secret biolabs” in Ukraine. Beijing’s disinformation efforts were on display in the run-up to the Taiwan general election in January, making use of publicly available information for political disruption — also something that Russia has done related to the war in Ukraine — to stoke fear of the island’s security situation and amplify mistrust in the elected government and U.S. reliability and readiness to come to Taiwan’s aid.

China-Russia alignment in the censorship and disinformation spaces has far-reaching implications for the global security landscape. While both Beijing and Moscow pursue cooperation and learning opportunities in these spaces primarily to safeguard regime stability in their respective countries, efforts to shape the global information space in favor of authoritarian states should not be underestimated. Especially as AI-powered disinformation campaigns become more widespread, the scale and sophistication of campaigns not only threaten democratic elections but can also have significant implications for shaping narratives in either Beijing or Moscow’s favor in conflict zones or key areas of interest for the United States and its allies. While there exist clear historical limitations and mistrust between Russia and China, alignment against the United States to safeguard harmful narratives at home while shaping discourse abroad in favor of authoritarian norms presents a clear challenge to the U.S.-led system. During this year’s Lunar New Year call between Putin and Xi, which took place one month ago, Xi reportedly said the two countries should “pursue close strategic communication to defend their sovereignty and security and oppose outside interference in their internal affairs.”