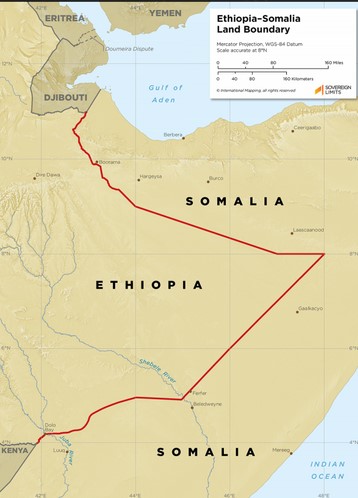

Ethopia-Somalia (sovereignlimits.com)

STRATEGIC ASSESSMENT. Tensions continue to mount in the Horn of Africa as Ethiopia looks to move ahead with a deal that would grant Addis Ababa twelve miles of sea access along the coast of Somaliland for the next 50 years, where it plans to construct a naval base. Reporting suggests that, in exchange for access to the port of Berbera, Ethiopia would look to recognize Somaliland as an independent country at some point in the future, although Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed has been reluctant to discuss the details of any forthcoming agreement. There is also part of the deal that will afford Somaliland a stake in Ethiopian Airlines. Somaliland, a former British protectorate located along the southern coast of the Gulf of Aden and bordered by Ethiopia to its south and west, seceded from Somalia in 1991, but is not internationally recognized as an independent state. Somalia has called the growing ties and military cooperation between Ethiopia and Somaliland “an act of aggression” and an assault on its territorial integrity.

The proposed deal has been backed by the United Arab Emirates (UAE), which remains a strong supporter of Abiy, Ethiopia’s Prime Minister, who has been the driving force behind this proposed deal. Earlier this week, Ethiopian Field Marshal Birhanu Jula met with Somaliland’s Major General Nuh Ismael Tani in Ethiopia’s capital, Addis Ababa. There is speculation that if Ethiopia eventually recognizes Somaliland, Abu Dhabi could quickly follow suit. The UAE has increasingly sought to expand its influence in the Horn of Africa, often working behind the scenes to position itself favorably among shifting alliances and partnerships. As has been reported, in 2019 Ethiopia bought a 19 percent stake in the Port of Berbera, Somaliland retained 30 percent, and Dubai firm and port manager DP World is contracted to hold 51 percent. The move in Somaliland could be an effort by UAE to diversify its investments in ports, since the port of Aden is facing significant logistical challenges as a result of the Houthis campaign against commercial shipping.

In response to what it views as a highly provocative move, Somalia recalled its ambassador to Ethiopia last week. Mogadishu has also called upon the African Union and the United Nations Security Council to convene meetings on the issue. Both the Organization of Islamic Cooperation and the Arab League sided with Somalia on the matter, with the latter releasing a statement that called on Ethiopia “to abide by the rules and principles of good neighborly relations” and to “respect the sovereignty of [neighboring] countries and not to interfere in their internal affairs.” The Arab League also warned that the agreement could contribute to the spread of extremism. While the UAE is backing Somaliland, Egypt and Türkiye are supporting Somalia, with Ankara calling for direct negotiations between Somalia and Somaliland. Both Egypt and Eritrea have shown concern about the possibility of an Ethiopian naval base in the region. Somalia’s President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud met Monday with his counterpart in Eritrea, Isaias Afwerki. Ethiopia lost sea access in 1991 after the littoral Eritrea declared independence and seceded following three decades of fighting. Ethiopia and Eritrea have a long history of conflict, even as the countries cooperated to combat the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) in Ethiopia’s recent bloody civil war that lasted from November 2020 to November 2022. Between tensions over the Somaliland agreement, Eritrea’s dissatisfaction with the terms of and its general exclusion from the Ethiopia-TPLF peace deal, and Ethiopia’s amassing of troops near the Eritrean border in November, fears have re-emerged that conflict could be reignited in the coming year.

The current crisis was foreshadowed months ago when, in mid-October, Ethiopian media aired a pre-recorded speech by Abiy to the parliament focused on the importance of access to the Red Sea for the landlocked country. Eritrea went on the defensive, believing the statement meant that Ethiopia might try to seize part of its territory. The announcement set off alarm bells in Washington, prompting U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken to urge all countries in the region to respect the independence, sovereignty, and territorial integrity of states throughout the Horn of Africa. But with the United States focused on conflicts in Ukraine and Gaza, it possesses far less diplomatic and political bandwidth to remain engaged in other parts of the world, including Africa. Any time political elites begin making overtures to historical claims, these should be taken seriously, in order to prevent the mobilization of forces and dampen the prospects for escalation. Other existing issues are likely to play a role too, including the ongoing struggle over the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), where Cairo and Khartoum are opposed to Addis Ababa’s project arguing it will deprive them of access to the Nile River.

Ethiopia currently relies on Djibouti as a major trade partner, as 95 percent of Ethiopia’s imports and exports pass through Djibouti. Addis Ababa has looked for ways to diversify its trading partners in the region and has explored options with both Sudan and Kenya for sea access in the past. There are reports that Prime Minister Abiy is facing pressure internally in Ethiopia, particularly on the heels of the conflict in Tigray, which devastated large swaths of the country and led to a humanitarian disaster. In addition to a precarious economy, there is growing instability in the Amhara and Oromia regions. As 2024 begins, Ethiopia was featured on several “conflicts to watch” lists, suggesting that many security experts see the country’s political situation as inherently unstable and believe a return to violence could be imminent if conditions remain unchanged.