Hezbullah Lebanon

STRATEGIC ASSESSMENT. As their offensive continues in the Gaza Strip, Israeli officials remain focused on the controlled escalation underway with Lebanese Hezbollah along the Israel-Lebanon border, which threatens to increase in the near-future. Israeli leaders and strategists assess that Lebanese Hezbollah, heavily armed and funded by Iran and far larger and more capable than Hamas, has the ability – and perhaps the intent – to conduct a significant attack into northern Israel. Months before October 7, Hezbollah leaders said that their movement intended to invade the Galilee and take over Israeli communities. Israeli leaders and commanders want to re-establish a significant buffer zone along their northern border that will provide ample warning of an attack by Hezbollah units. The Lebanese militia group has not fully joined Hamas’ battle against Israel as some initially feared, largely limiting its actions to cross-border rocket and artillery attacks into northern Israel. While these exchanges appeared to be predicated on an unstated rules of engagements between Hezbollah and the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) to limit attacks to military targets, civilian casualties have been incurred on both sides in recent weeks. 80 thousand Israeli residents have been evacuated from northern Israel to avoid the crossfire. Israeli leaders argue that the residents will not return to their homes unless Hezbollah agrees to retreat from the border. Meeting with northern Israeli mayors and municipal leaders on December 6, Israeli Defense Minister Yoav Gallant said that the government would not encourage the northern Israel residents to return home before Hezbollah pulls back to the Litani River 18 miles north of the UN-delineated border, known as the “Blue Line.”

Israeli leaders believe that international law supports their accusations that Hezbollah’s border encroachment violates the internationally recognized terms of a ceasefire that ended the 2006 Israel-Hezbollah war. UN Security Council Resolution 1701, which marked the end of that war, called for “the establishment between the Blue Line and the Litani river of an area free of any armed personnel, assets, and weapons other than those of the Government of Lebanon and of UNIFIL [the United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon].” The area has seen an uptick in Hezbollah activity since last spring, as the group erected tents inside Israel’s side of the Blue Line and fired an anti-tank rocket across the line. Lebanon’s Prime Minister Najib Mikati stated recently that Lebanon was committed to fully implementing Resolution 1701. However, Lebanon’s government and armed forces are not strong enough to constrain or disarm Hezbollah, enabling the group’s militia to gradually entrench itself in positions directly overlooking Israel’s border communities, well south of the Litani River. Still, Hezbollah’s opposition to withdrawal puts the movement in open violation of a UN Security Council Resolution that is backed by Beirut, rendering Hezbollah vulnerable to diplomatic and political pressure from within and outside Lebanon to accede to Israel’s demands that it withdraw from the area. Prospects for the United States or France to bring the Security Council together to update 1701 – for instance, by expanding the mandate of UNIFIL peacekeepers to constrain Hezbollah from further violating the ceasefire terms – are limited by the threat of a Chinese or Russian veto.

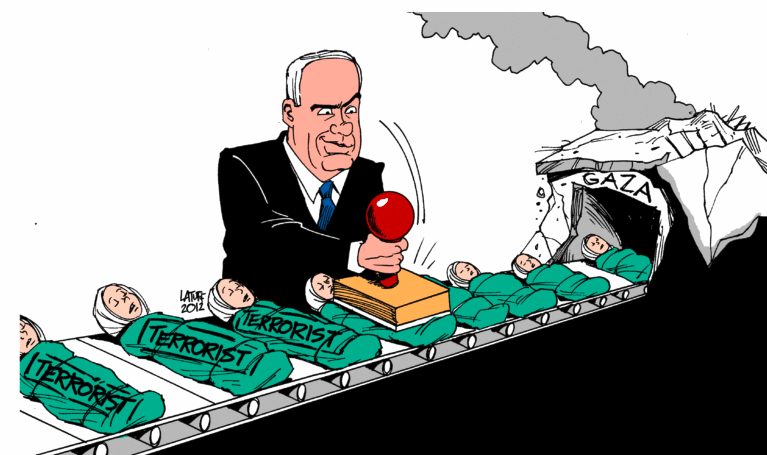

Israeli leaders and commanders have openly threatened to attack Hezbollah if it remains in its current position on the Israel border. In doing so, Israel is signaling to a broad range of Lebanese actors and the wider Lebanese population – many of whom consider Hezbollah an Iran-supported “state within a state” – that the IDF is capable of inflicting significant destruction on Lebanon unless its leaders insist that Hezbollah pull its forces from the border areas. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu threatened to turn Beirut “into Gaza” if the group escalates its rocket exchanges into a full-fledged war with Israel. Yet, with the IDF still heavily engaged in Gaza, Israeli threats are likely intended to stimulate other concerned international actors to persuade Hezbollah to relent. Opening up a major front with Hezbollah would represent a dangerous escalation in the current war that could cause Hezbollah to unleash its arsenal of an estimated 150 thousand Iran-supplied rockets and missiles on Israeli cities.

Opening a new front in Lebanon would worsen strains between the Netanyahu government and U.S. officials, the latter of whom have focused intently over the last two months on preventing the war from expanding into a broader regional conflagration. In November, U.S. Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin reportedly warned his Israeli counterpart, Gallant, not to escalate tensions with Hezbollah. U.S. presidential energy advisor Amos Hochstein made a similar warning during an early November visit to Beirut. Washington also has leverage to dissuade Israeli leaders from launching a major offensive against Hezbollah. Israel requires significant U.S. munitions resupply to conduct its offensive in Gaza effectively, and its need for U.S. weaponry would grow exponentially to deal with Hezbollah’s extensive arsenal. The near-certain U.S. opposition to any Israeli plan to escalate against Hezbollah supports analyses that assume Israel’s threats to attack Hezbollah are intended to mobilize international and regional diplomacy, rather than representing concrete military intentions.

If Israel’s intent is to draw international diplomats into the equation to promote a compromise, there are signs its strategy might be bearing some fruit. Reflecting Israeli unrest over Hezbollah’s position along the northern border, Hochstein, who helped negotiate the maritime boundary between Lebanon and Israel, sought to broaden his November discussions in Beirut to include the two countries’ land borders. Land border talks would necessarily also encompass discussions on how to compel Hezbollah to pull its militia back from the border. Since mid-October, France, the former Lebanon mandate power that still has significant influence there, sent three high-level officials to Beirut: foreign minister Catherine Colonna, defense minister Sébastien Lecornu, and President Macron’s personal envoy to Lebanon, Jean-Yves Le Drian. The officials highlighted the need for Lebanon’s leaders to address Israel’s border concerns and promoted extending the term of the Lebanese armed forces commander, Joseph Aoun, beyond January 2024. In early December, the head of France’s foreign intelligence service, Bernard Émié, in coordination with regional stakeholders such as Saudi Arabia, visited Beirut to push for an Israel-Hezbollah ceasefire and a Hezbollah withdrawal across the Litani. Hezbollah rebuffed the French officials, insisting it would stop striking Israel only after the Gaza conflict ended. Yet Émié, a former ambassador to Lebanon, also advanced a proposal that appears to be gaining traction – that Hezbollah withdraws its elite Radwan unit, rather than all of its forces, to the Litani. Though the proposal might be an attractive compromise for Israel, some have criticized its assumption that the Radwan unit would not later reposition itself closer to the Israel border. The French plan also, perhaps unrealistically, counts on the Lebanese army and UNIFIL to enforce the arrangement. Still, the entry of several major powers into discussions on Israel-Lebanon border security suggests that an IDF escalation against Hezbollah will not likely materialize, at least in the near-term.