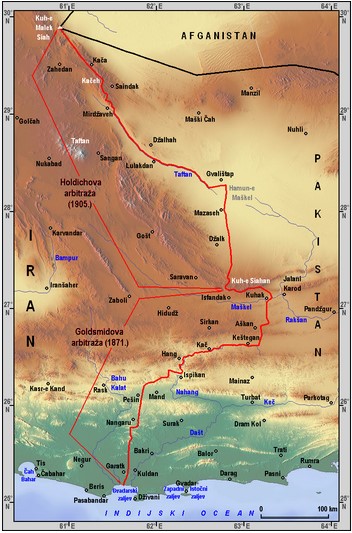

Iran-Pakistan border map (Wikipedia)

STRATEGIC ASSESSMENT. Iran and Pakistan have exchanged rocket and missile attacks over the past few days, with Tehran and Islamabad claiming, respectively, to be targeting their own nationals in militant groups operating on each other’s territory. Iran targeted training camps operated by Jaysh al-Adl, a Sunni separatist group operating in the Pakistani border province of Balochistan. Jaysh al-Adl, comprised of militants that splintered off from the terrorist group known as Jundullah, is believed to be behind an attack against an Iranian police station last month in the town of Rask, located in Sistan and Balochistan Province, which killed eleven Iranian security personnel. Pakistan withdrew its ambassador from Iran in a sign of protest and then on Thursday, used drones, rockets, loitering munitions, and standoff weapons to strike Baloch separatists based in southeastern Iran, killing at least nine. The Iran-based Baloch separatists targeted by Pakistan have been active on Pakistani soil in the past. Insurgencies by Baloch separatists have long occurred on both sides of the border and at a consistent pace since 2003. In Pakistan, Baloch separatists operating as part of the Balochistan Liberation Army (BLA) have attacked Chinese targets on several occasions, destabilizing the country and scaring off potential foreign direct investment at a time when the economy is in dire straits.

Despite launching an attack against targets in Iran the day after the Iranian attack against Pakistan-based militants, Islamabad’s statement explaining its response seemed designed to deescalate the situation, describing its action as “highly coordinated and specifically targeted precision military strikes.” The statement went on to say that “the sole objective of today’s act was in pursuit of Pakistan’s own security and national interest.” Follow-up statements by Pakistan’s military and Iran’s foreign ministry have also described a brotherly relationship between the two countries. China, Türkiye, and Japan, among other countries, have called for calm, and the United States said it is monitoring the situation and does not want to see escalation. It remains unlikely, though not impossible, that either Iran or Pakistan would choose to escalate the conflict, given the number of other domestic and regional issues each country is grappling with. Even minor escalation is worrisome, given Pakistan’s status as a nuclear power. Iran’s attacks in Syria, Iraqi Kurdistan, and Pakistan could be in response to internal domestic political pressure resulting from the attack in Kerman claimed by Islamic State (IS) in early January. In that attack, which took place during a commemoration for General Qassem Soleimani, the former head of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps-Quds Force (IRGC-QF), who was killed in a U.S. drone strike in January 2020, nearly 100 Iranians were killed and another 284 wounded. Jaysh al-Adl was initially believed to be a potential suspect in the Kerman bombings that IS ultimately claimed. Iran has since arrested 35 people and has claimed that its strikes in Syria and Iraq were targeting Islamic State operatives and an Israeli intelligence outpost.

Some analysts believe the flurry of attacks over the past three days was intended as a weapons test of sorts, a demonstration of Iran’s ballistic missile capabilities, intended for an audience in Israel. In the Syria strike, Iran allegedly used one of its most advanced and longest-range missiles, the Kheibar Shekan. Even though Pakistan does not wish to escalate the conflict with Iran, Islamabad does not want to appear weak to its eastern neighbor and longtime rival, India. The Pakistani military, which plays a major role in its national political scene, also likely believes it cannot afford to look weak to its domestic population ahead of next month’s scheduled general elections. Beijing is a longtime ally of Islamabad and, given its economic investments in the country, especially those linked to the Chinese Communist Party’s signature foreign policy centerpiece known as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), has a vested interest in ensuring security and stability in Pakistan.

Whatever happens next, it is likely that the Iranian-Pakistani border will remain a flashpoint in Southwest Asia, with both countries forced to dedicate more personnel and resources to securing their borders. This could make both countries more vulnerable elsewhere. Pakistani security forces have struggled to contain the BLA, while also battling an ongoing terrorist campaign directed by the Pakistani Taliban and other jihadist groups based in the country. Meanwhile, while Iran has enjoyed success managing its “axis of resistance” in the ongoing conflict related to Gaza, the regime in Tehran is unpopular domestically, following ongoing women-led protests within the country related to the September 2022 death of Mahsa Amini while in the custody of the “morality police.” The 22-year-old woman had been arrested for what the authorities claimed was improper dress for refusing to wear a hijab. Iran must also combat a persistent threat from IS and its regional affiliates and branches, including Islamic State Khorasan (ISK) in neighboring Afghanistan. Moreover, Iran and Israel have been locked in a shadow conflict for years, with Israel believed to be responsible for sabotaging Iran’s nuclear program, while also reportedly ordering the targeted assassinations of several high-profile Iranian nuclear scientists. Taken together, this suggests that Iran is already at risk of being overstretched and will need to focus its resources on those issues it sees as an overarching priority, none more important than the survival of the regime. A fresh conflict with neighboring Pakistan would only serve to occupy more of Iran’s bandwidth while inviting further instability.