STRATEGIC ASSESSMENT. Indonesian companies are raising their concern over how the rupiah’s weakness is raising their costs. The currency was the main agenda at a closed-door meeting between members of the Indonesian Chamber of Commerce and Industry, known as Kadin, and Bank Indonesia Governor Perry Warjiyo.

“We want to get direct answers from Bank Indonesia,” Kadin Chairman Arsjad Rasjid told reporters after the meeting, as cited by Bisnis Indonesia.

The weaker exchange rate has increased the cost of importing raw materials and capital goods for companies across various sectors, from food and beverages to aviation. More expensive foreign debt payments are also weighing on the businesses.

The rupiah has slid more than 6% against the dollar this year, the most in Southeast Asia after the Thai baht. The currency weakened 0.2% to close at 16,405 a dollar, near a four-year-low reached last week.

This question may be spinning in the heads of capital market and greenfield investors. Overall, Indonesia is an attractive investment destination for foreign direct investment (FDI), primarily because of strong domestic demand, abundant natural resources, a stable political situation and prudent macroeconomic and budget policy.

However, the latter has recently become a big concern for foreign investors. Although these are still important factors, we are becoming less dependent on foreign money in the capital market as our domestic source of funds has started to fill the gap. Reports of a slowdown in our economic performance have dominated recent news.

This trend was set in motion by the underperformance of household consumption, which was lower than expected. Household consumption growth used to beat or at least be on par with GDP growth before the pandemic.

From now on, we need to be cautious about that figure in terms of anticipating consumers’ purchasing power and behavior to understand whether this trend will be temporary or permanent. On the other hand, we can be 100 percent sure that the contribution of household consumption to Indonesia’s economy will never get close to 60 percent again.

According to James Guild, Adjunct Fellow at S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies in Singapore, as he prepares to take office later this year, Indonesian President-elect Prabowo Subianto has begun unveiling a bold vision for how the national economy will develop under his leadership. And a big part of this vision involves increased public spending which will be paid, in part, by more government borrowing. It was widely reported in recent weeks that the goal was to increase public debt to 50 percent of GDP over the next several years.

This was quickly walked back, with prominent figures including current ministers, former ministers, and members of Prabowo’s transition team stating that there are no concrete plans to increase the debt level to 50 percent of GDP, and that the incoming government will observe prudent spending policies. This was clearly done to allay doubts about Prabowo’s commitment to fiscal discipline, as the rupiah has been weakening recently and some people believe that is because investors are skittish about Indonesia going into budget-busting mode to meet big campaign spending promises in the years ahead.

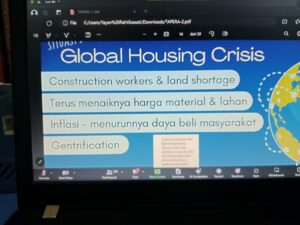

According to Shalhhakka Dimar Farrakhy, Audit Board of Indonesia; and Muhammad Rafi Bakri, Audit Board of Indonesia, the high demand for housing is not being met in Indonesia due to a lack of supply. For Indonesian people, a house can only be a house if it is on the ground — not in a flat or apartment. This increases market demand for land and property, which drives prices to increase. But rising prices are not being matched by proportionate income increases.

In response to this difficulty, the Indonesian government established the Public Housing Savings Management Agency — Tapera — in 2016. Due to socioeconomic developments, the government updated this regulation to now compel all Indonesian workers to participate in the Tapera program, with a monthly contribution of three per cent deducted from their salaries.

Salary deductions to fund Tapera enraged the public. Employers were also unhappy, as they will bear 0.5 per cent of the contributions charged to each employee. The community is still haunted by similar fund management cases, including Jiwasraya and ASABRI, which resulted in state losses of approximately Rp 40 trillion (US$2.4 billion).

Indonesia has a bigger revenue gap between small and big firms than other emerging markets, such as India, Mexico, the Philippines and Turkey, according to a World Bank report, with repercussions for the domestic economy.

Furthermore, those large companies failed to translate their revenue into as much employment as in other countries and were less efficient in allocating capital resources, the global financial institution noted, citing the manufacturing sector in Indonesia as a case in point, where the top 5 percent of firms accounted for 90 percent of revenue.

“[The top 5 percent of firms] control only 20 percent [of revenue] in Turkey, 35 percent in Mexico, 67 percent in India and 75 percent in the Philippines. These figures are much lower than the staggering 90 percent in Indonesia. It indicates an imbalance that could hinder competition and innovation in Indonesia,” Alexandre Hugo Laure, a senior private sector specialist at the World Bank, said.