Bolstered by their persistent threat to Red Sea shipping traffic, the Houthis have emerged as the most active components of Iran’s axis of resistance, even if Lebanese Hezbollah remains the most potent group within the broader proxy constellation. Iran has long cultivated a large network of allies to exert influence on the outcome of regional crises such as the Israel-Hamas war. Currently, Iranian proxies are working to counter U.S.-backed Israeli efforts to end Hamas’ administrative and military infrastructure in the Gaza Strip. The Houthis, also known as the Ansrallah movement, have thwarted a nearly decade-long Saudi-led military effort to roll back their control over northern and central Yemen. Unlike other Iranian allies in Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon, the Houthis have not limited their targets to Israeli or U.S. forces over the course of the war in Gaza, but have also targeted commercial ships with ties to dozens of different countries.

While targeting U.S. and coalition naval vessels and ground targets in Israel, Houthi land-attack cruise missile and armed drone attacks were consistently intercepted and did not affect U.S. or Israeli policies toward the war. In mid-November, the Houthis shifted to targeting commercial ships in the Red Sea and off Yemen’s coast, directly threatening the pillars of global commerce. As a hallmark of their effectiveness, the Houthis compelled U.S. diplomats to quickly assemble a new Red Sea maritime security operation. The Houthis have sought to justify the assaults as an effort to support the people of Gaza by depleting Israel’s war-making capacity, claiming they are only targeting ships linked to Israel or carrying goods there. However, not all the ships the Houthis have attacked have a connection to Israel. According to the commander of U.S. naval forces in the region, Vice Admiral Brad Cooper, 55 nations have direct connections to the ships that have been attacked, whether as the flagging state of the targeted ships, the site of production or destination for goods subject to Houthi threats, or due the nationalities of the mariners aboard the targeted vessels. Undaunted by the new U.S.-led maritime operation, the Houthis have continued their attacks.

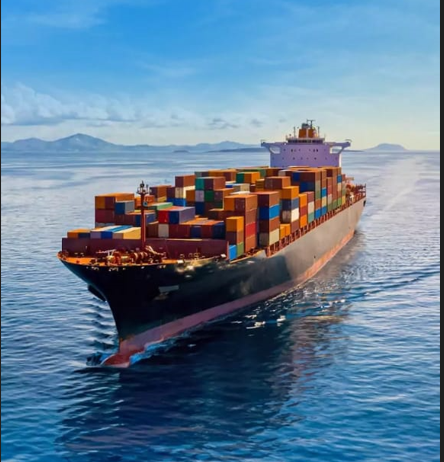

Houthi attacks on commercial Red Sea shipping have measurably affected global commerce and U.S.-led strategy toward the Mideast crisis. At least 18 major international shipping lines have altered their routes to avoid the Red Sea threat, often diverting to routes around Africa’s Cape of Good Hope. The adjusted route adds ten days, on average, to their voyages and entails higher fuel costs. The reorientation has also reduced commercial traffic through the Suez Canal by 25 percent, reducing a key revenue source for Egypt. Freight rates have almost tripled since the Houthi attacks on shipping began, adversely affecting the global economy’s battle against inflation. On the other hand, international economists note that shipping rates remain far lower than they were during the COVID-19 pandemic and assess that the global economy, at least for now, will be able to absorb the effects of the Houthis’ campaign.

The narrowness of the Bab al-Mandab Strait, the main access route to the Red Sea between the Arabian Peninsula and the Horn of Africa compels international shipping to pass slowly and in single file, with little room for maneuver. Transiting ships pose a ripe target for Houthi missiles, armed drones, and small boat or helicopter-borne raids. In the first half of 2023, approximately 12-15 percent of the world’s trade flows –including significant amounts of the global grain and liquified natural gas trade, as well as seaborne-traded oil – passed through the strait. Twenty-five commercial ships have been attacked by Houthi or Houthi-allied forces as of last Thursday, according to Cooper. Last week, a seaborne drone launched out of Yemen reportedly detonated within “a couple of miles” of U.S. Navy and commercial vessels in the Red Sea. Even though the Houthis have not, to date, dramatically upended the regional or global economy, U.S. and allied officials have decided that more forceful collective action might be needed to stop the Houthi attacks. In December, the United States assembled a multilateral coalition to provide security to commercial ships transiting the Red Sea. 14 participating allies named in the U.S.-led effort, termed Operation Prosperity Guardian, include Australia, Bahrain, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Germany, Italy, Japan, Netherlands, New Zealand, South Korea, Singapore, and the United Kingdom. 22 nations in total are contributing to the mission, Cooper said last week. The forces participating in the effort operate under the umbrella of the Combined Maritime Forces and the leadership of Task Force 153, an established but heretofore less well-equipped initiative led by the U.S. Navy focused on Red Sea maritime security. By forming the coalition, U.S. officials hoped to avoid a military escalation that could expand the Israel-Hamas war into a regional conflict or derail progress toward a political settlement to the decade-long war in Yemen. Although Saudi Arabia’s leaders declined to participate openly in Prosperity Guardian, they reportedly cautioned against escalation out of concern of re-igniting war in Yemen, where the Kingdom seeks to extricate itself in order to focus on advancing its Vision 2030 economic diversification program. U.S. officials initially presented signs that the policy might produce results: on January 4, Vice Admiral Cooper said that about 1,500 merchant ships have safely transited the Red Sea since Prosperity Guardian was launched.

Yet as 2023 ended, the maritime operation did not appear to have deterred the Houthis from targeting commercial or military ships in the Red Sea. Insisting they would keep up the attacks as legitimate support for Palestinian civilians suffering from Israel’s ground offensive in Gaza, the Houthis’ operations have drawn considerable support, as well as new recruits, from the highly pro-Palestinian population of Yemen. The movement has also been hailed by citizens throughout the broader region for remaining steadfast in the face of U.S.-led international threats.

Their stance has also pressured U.S. and allied leaders to more forcefully try to end the Houthis’ threat to global commerce. On December 31, the U.S. Navy destroyed three Houthi small boats whose crews had tried to board a container ship in the Red Sea, killing ten Houthi fighters. On January 1, amid reports of U.S.-UK discussions about possible military action against Houthi targets in Yemen, UK Defence Secretary Grant Shapps issued an editorial in the British press saying the United Kingdom was “willing to take direct action” to protect the Red Sea shipping lane. The editorial foreshadowed the issuance of a joint statement by all the named Operation Prosperity Guardian participants directly threatening to meet continued attacks with a forceful response, calling for “the immediate end of these illegal attacks and release of unlawfully detained vessels and crews. The Houthis will bear the responsibility of the consequences should they continue to threaten lives, the global economy, and free flow of commerce in the region’s critical waterways.” The signatories also said they were “determined to hold malign actors accountable for unlawful seizures and attacks.” With Houthi missiles still being fired at commercial ships following the statement’s release, the United States and its partners will soon face a choice whether to enforce their warnings or try to find an alternative diplomatic or other pathway short of armed conflict. Any coalition course of action is uncertain to succeed, or to forestall the continued expansion of the Israel-Hamas war throughout the region.