STRATEGIC ASSESSMENT. Indonesia, as the chair of the ASEAN Summit, is continuing efforts to bridge the gaps in the views and positions of all stakeholders in Myanmar, Foreign Affairs Minister Retno Marsudi said after attending a limited meeting with President Jokowi to discuss preparations for the ASEAN Summit at the Presidential Palace in Jakarta.

She said that resolving the conflict in Myanmar will not be easy, but Indonesia, as ASEAN chair, will continue to try and build communication. She revealed that the efforts made by Indonesia in Myanmar have included communicating with the Myanmar military, with the National Unity Government (NUG) of Myanmar, as well as ethnic armed groups, and several political parties there.

As for the decision reached during the previous summit, Myanmar will be invited to the 2023 ASEAN Summit at a non-political representative level because of the conflict that is still going on in that country, Retno said.

According to Joanne Lin, a co-coordinator of the ASEAN Studies Centre at ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute in Singapore and lead researcher (political-security) at the center on the Jakarta Post, as Indonesia hosts the first ASEAN Summit of the year next month, it will be reminded once again that its success as the ASEAN chair will be determined by how it manages strategic competition in the region and the challenges within the grouping such as Myanmar.

Much as the region is increasingly viewed as an arena of major power competition as noted in the State of Southeast Asia 2023 Survey Report, ASEAN is not without its options. In responding to the intensifying United States-China rivalry, the report has shown that the region favors the option of enhancing ASEAN’s resilience and unity to fend off pressure from the two major powers (45.5 percent of respondents).

A smaller proportion of respondents felt that ASEAN should continue its position of not siding with the two major powers (30.5 percent) or seek out “third parties” (such as the European Union, Japan, India, Australia, or the United Kingdom) to broaden its strategic space and options (18.1 percent). Such findings seem to indicate that Southeast Asian respondents desire ASEAN to exercise its agency and play a greater role in the region.

Chee Yik-wai, a Malaysia-based intercultural specialist and the co-founder of Crowdsukan focusing on sport diplomacy for peace and development on South China Morning Post, French President Emmanuel Macron’s recent comments about the European Union’s strategic independence amid big power conflict, while music to Beijing’s ears, displeased many proponents of closer transatlantic relations. Asean leaders such as Malaysia’s Anwar Ibrahim and Singapore’s Lee Hsien Loong have also called for cooperation over destructive rivalry.

The centrality of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations has been championed as a strategy in fending off the pressure the region comes under from big power conflicts. It is also an Asean quality that both the United States and China appear to support. But how the regional bloc can shore up its centrality is not easily answered.

Asean, with its members’ distinct cultures and plurality of religions, is not a homogenous community and the bloc has a bedrock principle of non-interference in each other’s domestic affairs. For Asean centrality to work well, the development of commonalities is essential.

Yet the lack of institutional efforts to promote cultural interaction among the people of Asean severely restricts this goal. Ironically, the superpowers that Asean leaders are so wary of seem to have done more to bring Asean citizens together, if only to align with their narratives and interests.

Government and think-tank representatives from Myanmar and its neighbours, including India and China, held talks in New Delhi as part of a secretive effort to de-escalate a bloody crisis in the army-run Southeast Asian nation, two sources said.

The talks this week were the second in a “Track 1.5” dialogue that started in Thailand last month and came as frustration grows within the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) bloc at the military’s failure to implement a peace plan it agreed to in April 2021.

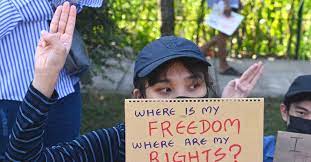

Gwen Robinson, Senior Fellow at the Institute of Security and International Studies, Chulalongkorn University, Thailand, and Editor-at-Large at Nikkei Asia on Fulcrum, a great irony emerging from Myanmar’s coup on 1 February 2021 is how it enabled military chief Min Aung Hlaing to achieve something no modern Myanmar leader could ever do: unite a fractious society. In a country long dominated by its Bamar majority yet riven by ethnic, social and religious tensions, resistance groups driven by popular fury bridged traditional divides to come together in the post-coup period.

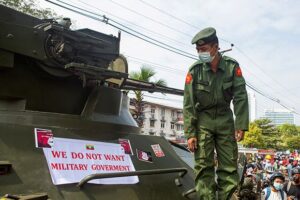

Yet in regional diplomatic terms, the coup has had the opposite effect. It has shattered the cohesion of the ten-member Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). Initial mediation efforts by ASEAN leaders led to the so-called Five-Point Consensus (5PC) with the junta leader in April 2021 to halt violence, recognise an ASEAN special envoy, allow dialogue between all parties, and grant access to humanitarian aid.

The 5PC, later rejected by Min Aung Hlaing who claimed he was following his own “five-point” plan to resolve tensions, has become an embarrassment for ASEAN, highlighting its collective policy paralysis. Indonesia, as the group’s rotating Chair for 2023, is trying to change that. But it is a monumental task. ASEAN’s decision to suspend Myanmar from sending political representatives to high-level meetings undermined its cornerstone principles of centrality and non-interference in each other’s affairs – leaving the group in an open-ended “10-minus-1” configuration.

Meanwhile, Ved Shinde, research intern at the Asia Society Policy Institute in New Delhi on Lowy Institute, in early 1979, fearing the growing security cooperation between Hanoi and Moscow, China invaded Vietnam. A year earlier, the then-Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping met Singapore’s prime minister Lee Kuan Yew, asking for Singapore’s support against Vietnam. But, to his utter surprise, the canny Singaporean leader caught the equally perceptive Deng off guard.

Lee Kuan Yew admitted that Singapore was worried about Beijing’s ambitions to dominate the region more than Vietnam. In other words, China was Singapore’s most significant source of long-term concern. The point is that even before China’s economic transformation, Southeast Asian states were worried about living with a giant next door.

This brings us to the Quad, drawing together the Australia, Japan, India and United States. It’s not to say that the Quad must expect the ASEAN member states to choose between binary choices. Southeast Asian are adept at playing a polygamous game. Their geographical location and relative sizes do not afford them the liberty to pick clear sides.