BY:AIR

STRATEGIC ASSESSMENT-So far, the western world has slandered Islam as a terrorist, the fact is that terrorists were created by America.

The western world made terrorists as a project to destroy Islam, those of you who accuse Islam of being terrorists please open your eyes and use your brain to think rationally.

If your brain is sane you will see the real facts,Terrorists are not Muslims, they are made like Muslims.

Terrorist Recruitment The Crucial Case of Al Qaeda’s Global Jihad Terror Network

Two Americans Become Al-Qaida Media Strategists

There are a lot of different ways of promoting the terrorist message, but few people have been as successful at doing so as Americans Adam Gadahn and Anwar al-Awlaki.

Gadahn is a Californian who joined al-Qaida back in the late 1990s. He’s the plump, sometimes pedantic, star of al-Qaida’s earliest videos. Awlaki is a New Mexico native of Yemeni descent who has, in recent months, become the bane of counterterrorism officials’ existence.

What is important about both men is that they are among a select group of Americans who have joined up with terrorist groups and were elevated to senior positions within them. Both Gadahn and Awlaki now provide al-Qaida with insider’s knowledge of the United States — and that has helped al-Qaida and its affiliates develop a very sophisticated media strategy targeting possible American recruits.

The Different Approaches Of Gadahn And Awlaki

At a recent classified U.S. intelligence conference outside Washington, one analyst used a famous television commercial to explain not just the difference between Gadahn and Awlaki, but the evolution of al-Qaida’s media operation.

As the commercial started on the screen at the front of the auditorium, the voices were immediately familiar: “Hi, I’m a Mac, and I’m a PC,” it began. The audience burst out laughing. There was even a smattering of applause. The analyst had replaced the faces of the actors with the faces of Gadahn and Awlaki.

In the original ad, the PC is old-fashioned and a little geeky. The Mac is low-energy cool. Gadahn’s face was on the body of PC. And Awlaki was the Mac. You just need to listen to them to understand why.

“Barack, I know that as you slither snakelike into the second year of your reign,” Gadahn said in a recent videotape addressing President Obama, “as a purported president of change you are finding your hands full with running the affairs of a declining and besieged empire…”

Gadahn goes on in the same vein for about 40 minutes. One analyst said Gadahn isn’t just a stodgy PC; he sounds like a character out of The Lord of the Rings. Mia Bloom, a terrorism expert at Penn State University, agrees.

“He has this presence where it is very stiff,” she says. “He has the tendency to point a lot at the viewers and has this alienating character. He apparently is modeling himself after al-Qaida’s second in command, Ayman al-Zawahiri. And he has never been a very engaging speaker.”

As Bloom sees it, Gadahn doesn’t have any of Awlaki’s charisma. Awlaki comes off as someone who might be your favorite professor. He is soft-spoken and at least seems to be asking his listeners to think for themselves.

“If there is no compulsion in religion, why were battles fought?” he said in one recent audio posting. “I think that this is an issue that you need to have a clear understanding. The non-Muslims say that Islam was spread by the sword … is that true or not? Let’s talk about what happened and then you can make a judgment.”

Awlaki’s style is gently persuasive — like Osama bin Laden. Tens of thousands, maybe millions, have watched his lectures on the Internet.

“Unlike Gadahn, Awlaki has religious credentials and I think is viewed as a more mature character,” says Juan Zarate, a former deputy at the National Security Council during the Bush administration. “Adam Gadahn was always a teenage punk who happened to be there for al-Qaida at its zenith. He served a role, but not very well, frankly.”

Gadahn’s Story

The story of Adam Gadahn is fairly well known. He grew up on a goat farm in Southern California. His parents were hippies. He was home-schooled, big into death metal rock, and eventually found Islam.

Haitham Bundakji was a witness to Gadahn’s conversion at the Islamic Society of Orange County in the late 1990s. He was also a witness to Gadahn’s radicalization a short time later. “It didn’t take long before he had started spending time with the wrong kind of people at the mosque,” Bundakji says. There were a handful of angry, particularly devout Muslims at the mosque who immediately befriended Gadahn. “He came to the mosque by himself and he didn’t have family who were Muslim, so he was all alone.”

Gadahn spent most of his days hanging around the Islamic center. He performed the five daily prayers there. He found odd jobs to do. Bundakji says these young men, a bit older than Gadahn — in their 20s and 30s — took advantage of the new convert. They turned Gadahn against Bundakji, whom they saw as too progressive.

Bundakji says that back in 1997, Gadahn actually attacked him. Gadahn was arrested and charged with misdemeanor assault. He pleaded guilty and Bundakji barred him from the mosque for a time. By 1998, Gadahn and the other young men in his clique had drifted away from the mosque. A short time later, he left the U.S. and went to an al-Qaida training camp in Afghanistan.

Awlaki An Instant Phenomenon

Awlaki could not be more different. He came to the U.S. with his father, a Rhodes scholar who settled in New Mexico. Awlaki got a bachelor’s degree in engineering and a master’s, and was studying for a Ph.D. He was an imam in Virginia and San Diego and moved to Britain shortly after the Sept. 11 attacks. He became an instant phenomenon there. British Muslims were so used to having preachers with heavy accents who were dull and bookish that when Awlaki came, he was almost a revelation.

“They were just completely enthralled with Awlaki,” says Penn State’s Bloom. “Awlaki, who spoke completely unaccented English, was very charismatic and I think that in itself explains part of the difference between Gadahn and Awlaki.”

Awlaki didn’t start with a radical message. He used to sell popular CDs with the stories of the prophets — they were almost like Dr. Seuss stories for young Muslims, and he developed quite a following.

It wasn’t until he was imprisoned in Yemen in 2004 that his message got darker. And in just the past year, it has had real consequences. He inspired the man accused in the Fort Hood shooting, Maj. Nidal Hasan. He also allegedly helped train the young Nigerian who tried to detonate a bomb on a U.S. airliner on Christmas Day. U.S. intelligence officials say they now believe Awlaki is on the operational side of al-Qaida’s arm in Yemen, and he isn’t just a propagandist.

His ability to inspire young Muslims to violence has forced counterterrorism officials to contend with Awlaki’s YouTube audience and his keen understanding of how to transmit his message in the Internet age. He has given al-Qaida an amazing reach. Al-Qaida and its affiliates don’t have to go in search of recruits anymore — the recruits, inspired by Awlaki, find them.

Bringing An Understanding Of America

That’s just one of the reasons why counterterrorism officials are worried. Clearly one of the advantages Americans like Gadahn and Awlaki bring to al-Qaida is a deep understanding of the American audience — a sensibility they developed because they actually lived here.

And it cuts both ways. On the one hand, officials say it is a dangerous development because they now are looking for terrorists who, for example, lived in New York City and know how things work there, and that, in turn, could make it more vulnerable to attack.

But officials say there could be a good side to that, too. They are trying to understand whether the very American-ness of these people who sign up for violent jihad may mean they have an unconscious brake, that their time in the U.S. has imprinted them in such a way that they are only willing to take the violence so far.

One example is Faisal Shahzad, the Pakistani-American who wanted to blow up a car bomb in Times Square in May. Officials think it is telling that he had stashed a getaway car nearby. He seemed to have no intention of being a suicide bomber — although he later told authorities that he intended to keep bombing targets until he was killed by police in the act of doing so.

The question is whether that inclination to not commit suicide has to do with what happens to someone living in the U.S. for a long period time. Do such people develop a sense of life being too important to waste? The first-ever American suicide bomber killed himself only several years ago. He was a Somali-American from Minneapolis named Shirwa Ahmed. He killed himself in a car bombing in Somalia.SECURE.

The single biggest change in terrorism over the past several years has been the wave of Americans joining the fight — not just as foot soldiers but as key members of Islamist groups and as operatives inside terrorist organizations, including al-Qaida.

These recruits, a number of whom are profiled in this “Terror Made In America” series, are now helping enemies target the United States.

The list of American terrorists is growing, and they are coming from the unlikeliest of places: Miramar, Fla.; Charlotte, N.C.; Brooklyn; Albuquerque; and Winchester, Calif.

This series looks at a handful of what are arguably America’s most successful jihadis — people who have risen to a position of prominence in the world of radical Islam. They have emerged as masterminds, propagandists, enablers and media strategists who, because of their understanding of America, pose a new challenge for law enforcement.

One, Adnan Shukrijumah, was born in Saudi Arabia, reared in Trinidad and came of age in Florida. He is now considered one of Osama bin Laden’s top lieutenants. Samir Khan is a North Carolina man thought to have edited and created a new English-language magazine for al-Qaida’s arm in Yemen. Yousef al-Khattab was the founder of Revolution Muslim, an extremist group that operates openly in New York City.

He has since left the group. The organization has become a gateway for young Muslims looking to sign up for violent jihad. And Adam Gadahn and Anwar al-Awlaki are two Americans who have helped al-Qaida develop a savvy online presence that is attracting recruits from around the globe. Authorities had been so concerned about al-Awlaki, a radical cleric now living in Yemen, and his ability to recruit jihadis to attack the U.S. that they put him on a capture or kill list — essentially targeting him for assassination.

All of these people have brought uniquely American qualities to the groups they support. Shukrijumah’s path to power in al-Qaida reads like a typical American success story. He worked his way up. Khan’s magazine has a glossy American quality to it — from the jazzy headlines to the articles on how to pack for jihad — and he tested its prototype in the United States. Members of Revolution Muslim have openly demonstrated in support of al-Qaida, and its founders are converts taking full advantage of how easy it is in America to reinvent oneself. Gadahn and al-Awlaki learned how to reach an American audience by watching how it is done in America, firsthand.

Together, these Americans within their groups have changed the nature of the terrorist threat against this country: They are more threatening because they understand the United States better than the United States understands them.

Donald Trump’s favourite reply to any question on any subject under the sky—economy, Iran, terrorism, nukes, women, Ukraine — is usually this: “Nobody knows it better than me.” Let’s take this claim on face value and put a few questions to the omniscient President of the US states.

1) Who created Daesh, the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria?

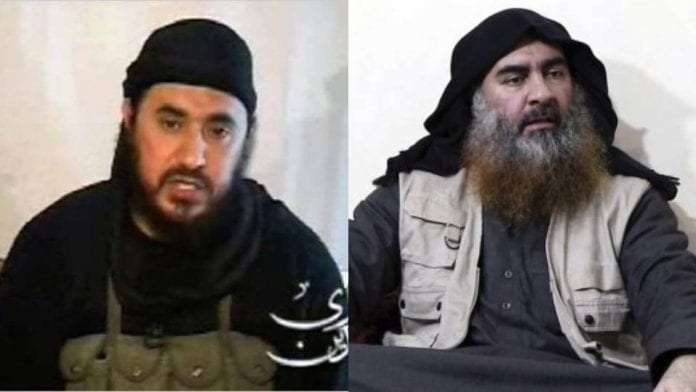

2) Who contributed to the rise of ISIS founders like Abu Musab al-Zarqawi and Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi?

3) Who started the chain of events that led to the creation of Mujahidins, then Taliban, then al-Qaeda, and finally the caliphate?

For those who have been following the arc of history since the Russian invasion of Afghanistan, there is just one answer to all these questions — the United States of America. A cursory reading of history would tell us that the US has been to global terrorists what Frankenstein was to his monster — the creator, the originator.

It is kind of cute to hear Trump gloat and boast after the US forces killed the self-proclaimed caliph, chief of ISIS, al-Baghdadi after a covert operation in Syria. Trump, who is in trouble at home because of impending impeachment by the Congress, has latched on to the development like an ecstatic child. In the euphoria of the victory, he has announced that al-Baghdadi died like a dog, a coward.

But, al-Baghdadi and his organisation would not have been such global threats if the US had blundered its way through the Middle East, wreaking havoc on its populations and creating monsters out of ordinary thugs.

A brief history of ISIS and Baghdadi

The ISIS of today was just a rag-tag group of jihadists led by an obscure Jordanian till 2002. Its founder, al-Zarqawi, after having disbanded his terror camps, funded by al-Qaeda, in Herat on the Iran-Afghanistan border was on the run, looking for hideouts in the Kurdish enclaves of Iraq.

In the winter of 2002, Zarqawi — a heavy drinker and brawler who had become a jihadi under the influence of Islamic preacher Abu Muhammad al-Maqdisi — was running a small camp of hardliners with a local group called Ansar al-Islam on the Iran-Iraq border. Nobody—not even Saddam Hussein’s intelligence officials — had heard of him.

On October 28, 2002, two assassins pumped seven bullets into a US diplomat in Jordan’s capital Amman. A few months later, the Mukhabarat, Jordan’s counterterrorism agency, was able to trace the killers to Zarqawi’s camp. In a few days, CIA spies were able to locate Zarqawi in Sargat, a hamlet in northern Iraq, and soon had his entire camp on their radar. As the head of the CIA unit tracking Zarqawi begged for orders to take him and the entire Ansar group down, the US top brass first dithered, and then finally said no (primarily because George Bush felt it would have weakened the case against its plan of hitting Saddam).

Instead, the Bush administration went to the United Nations and introduced Zarqawi, who nobody knew by then, as the al-Qaeda top boss in Iraq who had the blessings of the Saddam administration (a complete fabrication). With their folly, the US raised Zarqawi’s

stature, gave him free publicity that attracted hundreds of jihadis.

Several reports have established two facts since then. One, the Saddam administration would have destroyed Zarqawi and his Ansar group if it had credible information on its activities and hideouts. Two, contrary to the US propaganda, there was absolutely no link between the Baathists, al-Qaeda and al-Zarqawi (Saddam would have actually strived to destroy the terror groups). But, the US invaded Iraq on the basis of bogus claims of a link between the three, and fictitious assumption that Saddam was sitting on a pile of weapons of mass destruction (which were never found).

Soon after the US forces landed in Baghdad, Zarqawi became the face of Iraqi resistance. He started attacking the US forces, embassies of its allies, UN officials and Shiite clerics through daring suicide attacks, in the process becoming the rallying point for the Iraqi Sunnis and former officials of Saddam’s army who had been stripped of both income and dignity.

In the laps of the botched, unjustified US invasion of Iraq was thus born the Islamic State of Iraq, and its founder Zarqawi, a former drug peddler and alcoholic who could have been easily squished before he became a dreaded terror don.

Around the time Zarqawi was exploding bombs mounted on cars in Baghdad, Najaf and Fallujah, planning massive chemical attacks on Amman, a shy, unimpressive, bespectacled cleric was arrested by the US forces from an Iraqi town. Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi (original name Ibrahim Awad al-Badri) was picked up during a raid on his cousin’s hideout and sent to Camp Bucca on suspicion of being a hardliner. (A swab taken from his cheeks during this period was to be later used for confirming his death through DNA matching).

Till his arrest, al-Baghdadi was not even a small fish in the Jihadi Ocean. He was a preacher in a local mosque and his jihad was limited to the pursuit of deep insights into religion and Sharia. But, at Camp Bucca, he got the opportunity to mingle with some of the biggest terrorists of the period and influence them through his theological knowledge and interpretations of the Koran and Sharia.

In yet another folly that was to later cost the whole world dear, the US forces failed to foresee Baghdadi as a threat and released him from the camp after six months of incarceration. (Some accounts suggest he was held for five years). By the summer of 2014, Baghdadi had led his jihadis through the borders of Syria—where the US is embroiled in a war against the Bashar regime—and forged an alliance with the al-Nusra Front, the local arm of al-Qaeda. Once his outfit had drawn to its fold the best fighters in the region, Baghdadi unilaterally announced the merger of al-Nusra into his group and renamed it as Islamic State of Iraq and Syria. On July 4, 2014, he declared himself a caliph, leader of the 1.4 billion Muslims of the world.

The American Misadventure

The US blunders in the Middleeast and South Asia can be summed up in a single line: First it creates a monster, then, like the Indian demon Bhasmusara that turned against its creator, it gets into a fight with its creation. Ironically, after destroying its own monster, the US goes to the world claiming for itself the tag of the saviour.

But, the world has paid a heavy price for the US misadventures. In the 80s, it armed the Afghan rebels with shoulder-mounted rocket launchers and Kalashnikovs against the Russians. (The epic misadventure was immortalised in the Rambo series). The pioneer of its Afghan policy was a senator called Charlie Wilson, who channelled millions of dollars into the war through Pakistan. In the end, the Afghans turned against the Americans—like the Tamil Tigers against the Indian Peace Keeping Force. This flawed policy of supporting insurgency started a chain of events —the animosity with Afghans led to the birth of Taliban and al-Qaeda, the 9/11 terror strikes; the terror strikes led to the invasion of Afghanistan and bombing of Iraq; the havoc in Iraq led to the birth of ISIS—that has imposed a heavy price on the world.

The mindless, irrational invasion of Iraq on the basis of bogus intelligence, destabilised Iraq, led to the ouster of a dictator who was keeping terror outfits under a tight leash and delivered thousands of trained fighters and ex-army men into the waiting arms of terror groups. If the Middle East is today a jihadi den, it is primarily because of the US hubris, arrogance and blunders.

Incidentally, Zarqawi was initially interested only in fighting the Russians in Afghanistan and later Chechnya, but he swore revenge against the Americans after Bush bombed Kabul. Baghdadi, similarly, was just a cleric intent on enforcing a conservative form of Islam on his handful of followers. But, his incarceration during the Iraq offensive, gave him a larger cause—an uprising against the US and establishment of a caliphate.

But for the US, Zarqawi would have died in a pitched battle with Russians, or jailed in Jordon for dealing in drugs. And Baghdadi would have been preaching from the pulpit of a mosque in Samarra, railing against men who smoke or youngsters who watch women read news on TV without wearing an abaya. But, the US made them larger than life, global threats and terror icons.

That Trump is gloating about the fall of Baghdadi should go down as an irony of history.

*)Writer Global terrorist analyst and observer.